Archive

Clean Slate #3 : Catching up with billets – ups and downs

- Prettier If She Smile More by Toni Jordan (2023) Not available in French.

- The Insolents by Ann Scott (2023) Not available in English. Original French title: Les Insolents.

- The Last Red Tiger by Jérémie Guez (2014) Not available in English. Original French title: Le dernier tigre rouge.

- The Man Who Wanted to Be Simenon by Marianne Jeffmar (2004) French title: L’homme qui voulait être Simenon. Translated from the Swedish by Philippe Bouquet.

- Land Beyond Maps / Attack by Pete Fromm (2024) French title: Sans carte ni boussole / Attaque. Translated by Juliane Nivelt.

It’s time again to clear the To Be Written pile and give you an overview of books I’ve read or abandoned and that I don’t have either the inclination or the time to write a proper billet about. I know it’s not always flattering for the books that find themselves thrown together like this but limited reading and writing time calls for desperate measures.

Let’s start with one I quite enjoyed, Prettier If She Smiled More by the Australian novelist Toni Jordan, a book a lot better than its appalling cover.

Kylie is 43, has a boyfriend Colin, no children, a stable job at a pharmacy and a demanding family. Her life is turned upside down within a week as she finds out that Coin cheats on her, that the pharmacy she dreamt of buying when the owner retired has just been sold to a corporation and that her mother hurt her ankle and needs assistance for everyday life.

As she tries to juggle with all the challenges at the same time, it becomes obvious that something has to give and that she needs change.

I enjoyed reading the tribulations of Kylie with her immature brother, her spoiled mother, her more understanding sister and with her new boss and her religion based on KPIs and feedbacks. It’s definitely a good Beach and Public Transport book, a perfect light read. It’s my fourth Toni Jordan, I got what I hoped to find in her books.

Another book read a while ago, Les Insolents by Ann Scott, a French book despite the author’s English name. It won the Prix Renaudot in 2023 and it just fuels my weariness of literary prizes.

Alex, in her late forties, just out of a relationship with a married woman, decides to move out of her apartment in the Marais in Paris to rent a damp house in Brittany. She leaves behind her life and her two best friends, Margot and Jacques with whom she has a co-dependant relationship.

If I transpose this in the UK, imagine she’s moving from Camden to a remote place in Cornwall. And she doesn’t have a car.

She’s a musician, a famous composer of scores for the film industry, so she can work remotely. She’s clueless about the house, lives like a hermit, goes to the supermarket and walks along the beach. And of course she reflects on her life, her former drug addiction, blah, blah, blah.

The kind of milieu Virginie Despentes writes about but this is without Despentes’s spunk. So I was bored to death, never engaging with Alex and her clique and the whole morosity of the characters who are all victims of some trauma or other.

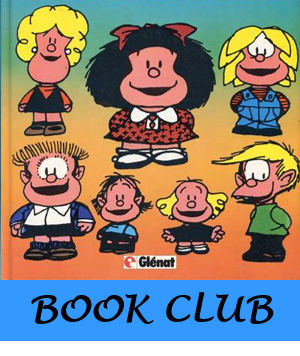

It’s also true that I have little patience and empathy with Parisians who move out of Paris to the great outdoors in Brittany, Normandy or Provence. It was our Book Club read for March and none of us liked it.

Totally different style, The Last Red Tiger by Jérémie Guez. I didn’t finish it, but that’s on me, not on the author.

The premises were interesting as the main character, Charles Bareuil signed in the Légion étrangère just after WWII and he lost his wife during the war.

He’s sent to Indochina where the war against Ho Chi Minh is intensifying and we know how that went for the French. Unable to accept the independence of this colony, the French government went into a war against a whole population, in a territory that favored the Vietnamese and it ended up in the Dien Bien Phu debacle. Zola would have a field day with the French colonial wars, I’m sure.

The plot thread is a competition, a cat-and-mouse play between Charles Bareuil and Tran Ông Cop, a Vietnamese sniper. It’s nicely done but I gave up when it became more about combats in the jungle than anything else. I couldn’t follow what was happening in those combats and well, it’s just not my cup of tea.

I was most disappointed by The Man Who Wanted to Be Simenon by Marianne Jeffmar. The cover is gorgeous and the blurb says:

“In a back alley in Paris, the police finds a dead body. Bernard Wouters, a well-respected teacher and unpublished writer had spent his life mimicking his idol, Georges Simenon. A journalist decides to investigate this mysterious death. She gets inspiration in Simenon’s work to solve the case”

Sounded intriguing, no? I expected a classic investigation but no. Instead of focusing on Wouters’s story and what led him in this back alley, Jeffmar adds another disturbing story about Wouters’ adolescent daughter, Marie-Jo.

She wrote a book set in Paris among prostitutes. She’s 16 and she’s a instant success à la Françoise Sagan with Bonjour Tristesse. But she’s not happy and it appears that her father was very controlling and I even wonder if he wasn’t incestuous. Basking in her literary success, that’s for sure.

It felt like the author wanted to pack too much into one book and failed to organize everything nicely. Plus it had aspects about prostitution and sex that I wasn’t keen on reading. I’m not a prude but the abuse against a prostitute, the murky relationship between father and daughter felt icky.

Something sounded off in this book. It’s was written in 2004 and I had a hard time understanding when it was set. The Thalys between Brussels and Paris is working but Wouters still pays with French francs, so it’s before the euro. It’s between 1997 and 2001, with early cell phones and still VHS cassettes.

The Paris described in the book sounds more like the Paris of the 1950s than the end of the 20thcentury. Same with the teenagers’ names. Marie-Jo’s friends are named Laurent, Jean-Paul and Claire, not names of babies born in the 1990s.

The whole thing felt off to me, unless there were clever clues about Simenon all over the book that I totally missed because I’m not a Simenon expert.

Let’s end up with a positive note: two short stories by Pete Fromm, Land Beyond Maps and Attack, one of my Gallmeister goodies.

Fromm is his usual self, picturing turning points in the characters’ lives, a moment that lights the way for them. This moment brings them clarity about who they are, whether they like it or not and where they’re going. We find Fromm’s recurring themes, young love, happy times in the wilderness and fatherhood.

Next billet will probably be about A Drink Before the War by Dennis Lehane.

Three beach-and-public-transport crime fiction books: let’s go to Sweden, Japan and Australia.

The summer holiday are coming soon, with lazy reading hours, waiting time in airports or train stations, train or plane travels and all kinds of noisy reading environments. That’s what my Beach and Public Transports category is for: help you locate page turners that help pass the time and don’t need a lot of concentration. So, let’s make a three-stops journey, starting in Stockholm with…

The Last Lullaby by Carin Gerardhsen. (2010) French title: La comptine des coupables. Translated from the Swedish by Charlotte Drake and Patrick Vandar.

It’s a classic crime fiction book that opens with a murder. Catherine Larsson and her two children are murdered in their apartment. She was from the Philippines, got married to Christer Larsson and they were divorced. He was deeply depressed and had no contact with his children.

Catherine lived in a nice apartment in a posh neighborhood in Stockholm. How could this cleaning lady afford such a lavish home?

The commissaire Conny Sjöberg and his team are on the case. The troubling fact is that their colleague Einar Ericksson has not shown up for work and hasn’t call in sick. Sjöberg looks for him and soon discover that Catherine Larsson and Einar Ericksson were close, that he used to come and meet her and play with the children. His sweater was in her flat.

Now the police are in a difficult position: their colleague is a suspect but Sjöberg thinks he’s a victim too. It complicates the investigation.

I enjoyed The Last Lullaby as the story progressed nicely, all clues clicking into place one after the other. I thought that the police team’s personal lives were a bit heavy. What are the odds to have on the same team someone with a traumatic past, someone who was raped and filmed, someone recovering of a heart attack and multiples divorces and affairs. It seemed a bit too much for me.

That minor detail aside, it’s a nice Beach and Public Transport book. Now, let’s travel to Japan for a very unusual story.

The House Where I Once Died by Keigo Higashino (1994) French title: La maison où je suis mort autrefois. Translated from the Japanese by Yukatan Makino. Not available in English.

The unnamed Narrator of the book and Sayaka met in high school and were a couple for a few years. Sayaka broke up with him when she met her future husband. He wasn’t too heartbroken, they never meant to spend their life together anyway. Seven years later, they reconnect at a high school reunion.

Sayaka contacts the Narrator a few weeks later and asks him to accompany her on a strange trip. When her father died, he left her with a key to a house. She knows that her father used to go there once a month but never talked about it. Since her husband is on a business trip, she doesn’t want to go alone. The Narrator accepts and they drive to a strange house in the woods by Matsubara Lake.

Sayaka doesn’t have any family left and has no memories of her early childhood. She wants her memory back and hopes that this house will trigger something in her.

The Narrator and Sayaka enter the house and start playing detective to find out whose house it is, why it is empty, where its inhabitants are and how they are linked to Sayaka’s father.

The House Where I Once Died is a fascinating tale and as a reader, I was captivated from the start. It’s like a children’s mystery tale, a strange house, clues in the rooms, a memory loss and weird details everywhere.

Step by step, along with the Narrator and Sayaka, we discover the truth about the house and its family. The ending was unexpected and the whole experience was a great reading time.

That’s another excellent Beach and Public Transport book at least for readers who can read in French, since it hasn’t been translated into English.

Now let’s move to Tasmania with…

The Survivors by Jane Harper (2020) French title: Les survivants.

This is not my first Jane Harper, I’ve already read The Dry and Force of Nature. This time, Jane Harper takes us to the fictional Tasmanian small town on Evelyn Bay. It’s on the ocean and along the coasts are caves that can be explored when the tide is low and that get flooded when the tide is high.

Kieran and his girlfriend Mia live in Sydney with their three-month old baby but they both grew up in Evelyn Bay. They are visiting Kieran’s parents Brian and Verity in their hometown. Brian has dementia and the young couple is here to help Verity pack their house to move Verity into an apartment and Brian goes to a medical facility.

This family is still haunted by the drama that occurred twelve years ago. Kieran was in the caves when a bad storm hit the town. Finn, his older brother who had a diving business with his friend Toby, went out to sea to rescue him. The storm turned their boat and they both drowned. Kieran has always felt responsible for the death of his older brother.

The storm devastated the town. The material damage was repaired. The psychological one, not really. That same day of the historical storm, Gabby Birch disappeared and never came back. She was fourteen and she probably drowned too. Her body was never found.

That summer, Kieran and his friends Ash and Sean were a tight unit who partied a lot. They were just out of high school and Kieran had secret hook-ups with Olivia in the caves. Gabby was Olivia’s younger sister and Mia’s best friend.

So, the group of friends who meet again in Evelyn Bay has this traumatic past in common. Olivia and Ash are now in a relationship. Olivia works at the local pub, with a student who is there for the summer. Bronte is an art student at university in Canberra. She waitresses at the pub too and shares a house on the beach with Olivia.

One morning shortly after Kieran and Mia’s arrival, Bronte is found dead on the beach. Who could have wanted to kill her? Old wounds reopen and everyone thinks about the storm and Gabby Birch’s unexplained death. The digital rumour mill runs freely on the town’s forum.

Are the two deaths related? How will Kieran deal with being in this town again in the middle of another dramatic event? What happens in those caves?

The Survivors isn’t an outstanding crime fiction book but it does the job. It’s entertaining and exactly what you need to read on a beach. Well, except for the fear you may get about rising tides and being stuck in caves…

The Survivors is my first of my #20BooksOfSummer challenge. Do you look for easy and entertaining reads for the summer or do you take advantage of the slower pace (no school and related activities, holidays…) to read more challenging books?

Crazy me, I’ll do 20 Books of Summer again #20booksofsummer22

I’m crazy busy and yet, I plan on doing 20 Books of Summer again.

Cathy from 746Books is the mastermind behind this event. I could pick only 10 or 15 books but I wanted to have 20 books to choose from and then we’ll see how it goes.

I already have the books from my ongoing readalongs with my Book Club, my sister-in-law, my Proust Centenary event and my non-fiction challenge. That makes seven books.

- In Cold Blood by Truman Capote (USA)

- Thursday Night Widows by Claudia Pineiro (Argentina)

- The Survivors by Jane Harper (Australia)

- Dead at Daybreak by Deon Meyer (South Africa)

- Fall Out by Paul Thomas (New Zealand)

- Days of Reading by Marcel Proust (France)

- Proust by Samuel Beckett (Ireland)

In August, I’ll be travelling to the USA, going through Washington DC, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia. I’ve already read The Line That Held Us by David Joy and Country Dark by Chris Offutt. I love to read books about the place I’m visiting, so I’ll be reading:

- Twelve Years a Slave by Solomon Northup (Louisiana)

- Where the Crawdads Sing by Delia Owens (North Carolina)

- Serena by Ron Rash (North Carolina)

- Above the Waterfall by Ron Rash (North Carolina)

- All the King’s Men by Robert Penn Warren (Southern Region)

- A Walk in the Woods by Bill Bryson (Appalachians)

- The Cut by George Pelecanos (Washington DC)

- The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead (Southern Region)

That’s eight more books and some of them rather long. I also wanted to do Liz’s Larry McMurtry 2022 readalong as I’ve had Lonesome Dove on the shelf for a while. That’s two chunky books in a beautiful Gallmeister edition.

And then I’ve selected four novellas, to help me reach the 20 books with one-sitting reads:

- Lie With Me by Philippe Besson (France)

- A Bookshop in Algiers by Kaouther Adimi (Algeria)

- The Miracles of Life by Stefan Zweig (Austria)

- Adios Madrid by Pablo Ignacio Taibo II (Cuba)

I’m not sure I’ll make it but who doesn’t love a little challenge? I’m happy with my choices, a mix of countries, of crime, literary and non-fiction and of short and long books.

Have you read any of the books I picked? If yes, what shall I expect?

If you’re taking part to 20 Books of Summer too, leave the link to your post in the comment section, I love discovering what you’ll be up to.

A Most Peculiar Act by Marie Munkara – the appalling Aboriginal Ordinances Act of 1918

A Most Peculiar Act by Marie Munkara (2014) Not available in French.

I’ve had A Most Peculiar Act by Marie Munkara on the shelf since 2018, when I bought it at Red Kangaroo Books in Alice Springs. I decided to read it for Lisa’s Indigenous Literature Week organised from July 5th to July 11th. Given my timeline, we’re still on July 11th when I write this, so I’m still on time.

I’ve heard of Marie Munkara on Lisa’s blog and read her autobiography Of Ashes and Rivers that Runs to the Sea. She’s one of the Stolen Generation people and she explains how she came back to her biological family.

A Most Peculiar Act is a satirical novel set in the Northern Territory in 1942. Each chapter starts with an excerpt of the Aboriginal Ordinances Act that date back to 1918. Basically, the Aborigines have no civil rights

We are in a remote place in the bush. The Aborigines live in two places, The Camp where families are gathered and The Pound, a place “enclosed with a high fence to keep the coloured females under eighteen in and everyone else out.”

They can’t live outside of The Camp, the young women must go the The Pound and they’re not allowed to welcome who they want at The Camp. They are all listed on the Register of Wards of State. The girls are placed as domestics in white families. Whitish babies are taken away from their mothers.

White civil servants operate The Camp and The Pound. The staff is composed of an Administrator, a Chief Protector of Aboriginals, four patrol officers and a Superintendent of The Pound. The wives also play an important part in the system. This little clique runs the Aboriginals’ lives according to the power bestowed upon them by the Aboriginal Ordinances Act and according to their incompetence, their prejudice and their meanness. They are all unworthy of their power.

We follow the fate of Sugar, a sixteen-year-old Aboriginal and of Ralphie, a patrol officer.

When the book opens, Sugar is pregnant and at the end of her pregnancy. She fails to hide in the bush when Ralphie and Desmond, the two patrol officers, come to the Camp. She’s sent to the hospital against her will. She wanted to deliver her baby in the bush, among her people. We soon learn that she had an affair with Ralphie and when she delivers twins, the whitest of the two is taken away and given to a white family.

Meanwhile, we see the absurdity of the interactions between the white management. The new Chief Protector of the Aboriginals, nicknamed Horrid Hump, is a teetotaller and a man with ambitions that far outweighed his capabilities. He fires Ralphie for drinking too much, condemning him to poverty. He hires Drew Hepplewaite to replace him. She’s mean-spirited and racist. She’ll go beyond her duty to make the Aboriginals’ lives miserable. She’ll also wreak havoc among the whites, destroying the carefully constructed balance between the people.

Each chapter is more absurd than the other and Marie Munkara uses her novella to point out the cruelty and the stupidity of the system. The Chief Protector of Aboriginals doesn’t protect them from anything and the assimilation policy ends up in changing people’s names or stealing their children. That’s why Aboriginal characters are named Rawhide, Horseshoe, Fuel Drum, Donkey Face or Pickhandle.

While Marie Munkara succeeds in showing the appalling system of these ordinances, I would have liked to learn more about the Aboriginal characters of the book. Also, for a French reader, the pidgin English spoken by the Aboriginal characters was difficult to read and to understand. It wasn’t a smooth read for this reader and it got in the way of fully enjoying the book. I might have missed some references too.

Out of the two Munkaras I’ve read, I’d recommend her autobiography before reading A Most Peculiar Act.

See Lisa’s review here.

Lantana Lane by Eleanor Dark – an intelligent comedy about a community doomed to disappear.

Lantana Lane by Eleanor Dark (1959) Not available in French (sadly)

This week is Bill’s AWW Gen 3, which means Australian Women Writers from Generation 3 and their books published between 1919 and 1960. See Bill’s explanations here.

This week is Bill’s AWW Gen 3, which means Australian Women Writers from Generation 3 and their books published between 1919 and 1960. See Bill’s explanations here.

Since I don’t know much about Australian literature, Bill kindly made me a list of books that met the GEN 3 criteria. After checking out which ones were available on the kindle, I settled on Lantana Lane by Eleanor Dark.

Great choice, if you want to know.

Eleanor Dark introduces us to the inhabitants of Lantana Lane, set in Dillillibill, a rural area of Queensland, the tropical part of Australia. They have small farms and mostly grow pineapples on their land that is not occupied by the sprawling lantana weed.

In this district it may be said with little exaggeration that if you are not looking at pineapples, you are looking at lantana.

You know what pineapples look like and this is lantana, a thick bush of weed:

Dark calls her characters the Anachronisms because they like farming and their small farms are against the flow of progress. Farming isn’t a well-esteemed profession.

We are not affluent people in the Lane. As primary producers we are, of course, frequently described by our legislators as The Backbone of the Nation, but we do not feel that this title, honourable as it is, really helps us much.

This hasn’t changed much over the last decades, has it? They work a lot and their income is uncertain and low. As Dark cheekily points out the three sections of the community which always keep on working whatever happens (namely, farmers, artists and housewives), are liable to get trampled on. Note the little feminist pique and the spotlight on housewives.

Only a few of farmers were actually born in Lantana Lane, several came from the city to live their dream of farming. We get to meet everyone, the adults, the children, the dogs, the utes and another weird vehicle named Kelly and finally Nelson, the communal kookaburra.

Each chapter is a vignette that either describes a family and their history, a special episode in their lives or a specificity of this part of Queensland. And what characters they are!

Cunning Uncle Cuth manages to stay with his nephew Joe without taking on a workload. Herbie Bassett let his contemplative nature loose after his wife died for there is no need to work for the material world when you can unclutter your life and enjoy gazing at nature. Gwinny Bell is a force of nature, a master at organization and obviously a superior intelligence. As the omniscient narrator points out, her skills are wasted in Lantana Lane.

I loved Aunt Isabelle, the older Parisian aunt of the Griffiths, who arrives unannounced, eager to live the pioneer life. Our communal aunt is an active, vivacious and extremely voluble lady of sixty-eight., says the Narrator, in the chapter Our New Australian. I loved her silly but kind behaviour. Her speech is laced with French mistakes in her English and French expressions (All accurate, btw. I seize the opportunity to tell my kind English speaking readers that the endearment mon petit chou refers to a little cream puff and not a little cabbage.) The most noticeable clue of her assimilation as a true Australian is that she will cry gladly: “Eh bien, we shall have a nice cupper, isn’t it?” Tea addict.

I laughed at loud when I read the chapter entitled Sweet and Low, about young Tony Griffith, his fife and his parents’ outhouse. I followed Tim and Biddy’s endeavours to grow things on their land and slowly take into account their neighbour’s agricultural recommendations.

The Dog of my Aunt is about Lantana Lane’s barmy characters, Aunt Isabelle’s arrival and her friendship with Ken Mulliner and I felt I was reading a written version of a Loony Tunes episode. Eleanor Dark has such a funny and vivid description of Aunt Isabelle’s travels to Dillillibill, her arrival at top speed on a Kelly driven by a wild Ken Mulliner that you can’t help chuckling.

Between the chapters about the people, Eleanor Dark inserted chapters about the place. There’s one about lantana and pineapples, one about the climate and cyclones, one about the serpents and one about the kookaburras and Nelson in particular. I wonder where the chapter about spiders went.

We understand that this tightknit community is in danger. The authorities are taking measurements to built a deviation, a bitumen road that will put them on the map. Pesticides invade agriculture, the trend is to create big farms. Eleanor Dark has her doubts about all these new methods and wonders what they will do to nature.

But this is a labour-saving age, and chipping is now almost obsolete. The reason is, of course, that Science has come to the rescue with a spray. The immediate and visible effect of this upon the weeds is devastating, though what its ultimate, and less conspicuous effects upon all sort of other things may prove to be, we must leave to learned research workers of the future.

Well, unfortunately, now, we know.

Eleanor Dark has a great sense of humour and Lantana Lane is a comedy. She mixes irony and humorous observations. She has knack for comedy of situation. She writes in a lively prose, a playful tone, shows an incredible sense of place and a wonderful tendency to poke fun at her characters. She points out their little flaws with affection and pictures how the community adapts and accepts everyone’s eccentricities. But behind the comedy, the reader knows that this way-of-living is condemned.

As usual, reading classic Australian lit is educational, vocabulary-wise. I had to research lantana, paw-paw, Bopple-Nut, pullet (although, being French and given the context, I’d guessed it was the old English for poulet) and all kinds of other funny ringing ones (flibbertigibbet, humdinger, flapdoodle…)

Visiting Lantana Lane was a great trip to Queensland, a journey I highly recommend for Dark’s succulent prose. For another take at Lantana Lane, read Lisa’s review here.

Note for French readers: Sorry, but it’s not available in French.

Our Tiny, Useless Hearts by Toni Jordan – Australian vaudeville

Our Tiny, Useless Hearts by Toni Jordan (2016) Not available in French.

Yesterday was quite stressful: I was waiting for my daughter to fly back from Singapore via London after her semester at her school’s campus there. She was on the Singapore-London redeye when one after the other, European countries closed their border with the UK due to this new COVID stain. Her journey from London to our home has been an adventure and of course, her luggage is missing. But in the end, all went well and thank God for technology, I was following her trip step by step.

Yesterday was quite stressful: I was waiting for my daughter to fly back from Singapore via London after her semester at her school’s campus there. She was on the Singapore-London redeye when one after the other, European countries closed their border with the UK due to this new COVID stain. Her journey from London to our home has been an adventure and of course, her luggage is missing. But in the end, all went well and thank God for technology, I was following her trip step by step.

But I needed a good distraction. I started to work on my best-of-the-year list and eventually decided that I needed a sugar-without-cellulite book to keep my mind off things. I killed two birds in one stone when I downloaded Our Tiny, Useless Hearts by Toni Jordan. It was the perfect distraction for the day and I reached the Stella stage of my 2020 Australian Women Writers Challenge. Brilliant.

When the book opens, Caroline and Henry just had a fight. They’re married and have two daughters, Mercedes and Paris. (I wonder how they would have named their boys. Aston and Rome?) Caroline discovered that Henry’s cheating on her with Martha, their daughter Mercedes’s grade three teacher. Henry is trying to explain to his daughters why he’s leaving with the teacher. Janice, Caroline’s sister is at their place, ready to take over and watch her nieces for the weekend and this is the scene she witnesses at her arrival:

When I get to Caroline and Henry’s bedroom at the end of the corridor, I’m faced with a scene of devastation. Henry’s suits are spread out over the unmade bed like a two-dimensional gay orgy: here a Paul Smith, there a Henry Bucks, everywhere a Zegna. The trouser-half of each and every one of them is missing its crotch and Caroline, chip off the old block, is peering over them with her reading glasses on the end of her nose and the good scissors in her hand. She’s still in her nightie, freshly foiled hair loose and a silk kimono draped over her shoulders. She looks forlornly at her symbolic castration and sighs, just like Mum did all those years ago. ‘What a waste,’ she says, as she shakes her head. ‘Maybe not super-helpful at this point, Caroline darling,’ I say. She shrugs. ‘These trousers failed in their primary duty, which is to contain the penis. They have only themselves to blame.’

Henry is actually leaving Caroline for Martha. He’s taking her to Noosa for the weekend. When Caroline realized where Henry takes Martha, she chases after them. She’s quite miffed that the mistress is going to Noosa when the wife went to Dromana. I checked what it meant in Australian standards and here’s my American translation: for his lover, Henry planned a trip to the Keys, Florida when he took his wife to a coastal town in Connecticut.

Meanwhile, the neighbours Lesley and Craig stop by, wondering what’s happening. They’ve heard the fight between Caroline and Henry and their nosiness got the better of them, they needed to meddle.

Janice is the self-conscious micro-biologist sister, she divorced Alec two years before and although she dumped him, she hasn’t recovered yet. After Caroline and Henry left, she settles with the girls and decides to sleep in her sister’s room to be near them. She’s quite surprised to find a naked Craig in the bed with her when she wakes up. Apparently, Caroline has secrets too.

Next morning, new discovery. Alec arrives on her doorstep for his planned visit to the girls. Janice didn’t know he was still in touch with Caroline and Henry.

And the show goes on, with a fast-paced plot with witty dialogues. There are laughing-out-loud dialogues, like the one when the adults talk about sex using a gardening analogy to protect the little ears that are sitting in the room. I enjoyed Jordan’s piques:

Honestly Caroline, let it go. What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.’ ‘That’s garbage,’ she says. ‘What doesn’t kill you joins forces with all the other things that don’t kill you. Then they all gang up together to kill you.’

I agree with Caroline. I dislike this “What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger” saying because I’m not sure it’s true. And it guilts people into thinking that if a tragedy makes them weak, they are wrong and should overcome it and feel stronger.

Janice is overwhelmed by all the people going in and out of the house and she struggles to avoid encounters between two wrong persons. She’s a peacemaker at heart and would like Caroline and Henry to patch things up for their daughters’ sake. And of course, things never go as she’d like and she has to be quick on her feet and adapt.

Our Tiny, Useless Hearts is an Australian vaudeville and it could be a theatre play with doors banging, husbands and lovers hiding behind doors or under the bed, misunderstandings, secrets, allusions and grand scenes. I would love to see this on stage.

You need to be in the right mood to enjoy this kind of book. And I was in the right frame of mind. I had a lot of fun reading it, it didn’t require a lot of brainpower but kept my mind busy and more importantly, it kept worry at bay. Mission accomplished, Toni Jordan!

The Catherine Wheel by Elizabeth Harrower – toxic relationship at its finest

The Catherine Wheel by Elizabeth Harrower (1960) Not available in French.

“I felt as if something was killing me. The pressure of his personality.”

The Catherine Wheel by Elizabeth Harrower is set in London in the 1950s. Clemency James, 25, is from Sydney and is in London to study for the bar by correspondence. (Why couldn’t she stay in Australia if she were to study by correspondence anyway is a mystery to me) She has a room in a boarding house, where she shares a bathroom and a kitchen with other tenants. Her room is her safe harbor, her place to study, work and teach. Indeed, her life is split between studying, giving French lessons, tending to her domestic duties and meeting with her friends until Christian Roland and his so-called wife Olive move into the boarding house.

The Catherine Wheel by Elizabeth Harrower is set in London in the 1950s. Clemency James, 25, is from Sydney and is in London to study for the bar by correspondence. (Why couldn’t she stay in Australia if she were to study by correspondence anyway is a mystery to me) She has a room in a boarding house, where she shares a bathroom and a kitchen with other tenants. Her room is her safe harbor, her place to study, work and teach. Indeed, her life is split between studying, giving French lessons, tending to her domestic duties and meeting with her friends until Christian Roland and his so-called wife Olive move into the boarding house.

They’re an odd couple, Olive is a lot older than Christian and she left her husband to follow him to a strange life in London. Christian is handsome, tortured and uses twisted ways to take people over. He’s full of unrealistic dreams like becoming a star actor at the Comédie Française in Paris when he’s not French and doesn’t even speak the language fluently. But he’s certain that he’s entitled to a higher standard of living and that being poor is totally unfair to him.

At the beginning, Clemency isn’t particularly interested in befriending them but Christian and Olive worm themselves into her life. Christian manipulates her into giving him free French lessons. Olive is especially friendly and diffident. Clemency is more and more drawn to Christian in spite of her and he pursues her relentlessly. Olive is consumed by jealousy –according to Chrisitian—and the reader never knows whether she’ll surrender or turn violent or whether it’s all in Christian’s imagination because he wants to live in a world where women fight over him.

The whole novel is told by Clemency and it is the slow destruction of a young lady who thought herself strong enough to get close to Christian’s flame without burning her wings and fails spectacularly.

It’s the tale of a neurotic relationship based on a fight between two minds. Clemency’s mind is determined not to be conquered and it acts as a red flag to Christian’s mind, pushing him to use every trick that his sick mind makes up to win her over. It’s not the assault of a lover consumed by love. It’s the assault of a deranged and narcistic man who wants to conquer and bask into Clemency’s surrender.

I looked it up, “the Catherine Wheel or breaking wheel is an instrument of tortuous execution originally associated with Saint Catherine of Alexandria”. This is exactly what Christian –funny name for a character who uses a mental instrument of torture compared to one used to execute Christians— is doing to Clemency. He’s killing her free will, her independence of mind. He tries to cut her from her friends. He embarks her in his journey towards self-destruction and madness. He lies, he cheats, he drinks, he believes in the wildest and most unrealistic schemes, like the one about Paris.

All in fair in love and war? For Clemency, all is unfair in this story but she’s not necessarily a likeable character. She seems untethered, detached from everything and living like a fish out of the water. I wanted to shake her up and seeing her so passive, even at the beginning, before she got drunk on Christian, got on my nerves.

Reading this was a mini Catherine wheel to me. I abandoned the book twice before eventually finishing it. I started to write my billet about why I had given up on it and realized that I’d already invested enough time in it and I needed to read it entirely to write this billet.

I didn’t like to read about Clemency’s destruction even if I wasn’t invested in the characters. I have no patience for tortured relationships (hence my profound dislike of Wuthering Heights) but here, I couldn’t help thinking that I was witnessing the appropriation of one’s mind by another person, that it happens in real life and that the writer was describing a frightening mechanism.

We’ve all known people whose behavior changed drastically after they started seeing or befriending someone new. We’ve seen people giving their money, losing their good sense over someone or acting against their best interest. This is what Harrower’s book is about. The mechanism of the relationship between Clemency and Christian is applied to a love relationship in this novel. It could also be between friends or family members.

Harrower’s tour de force lies in the minutia of her description. Christian’s manipulation is gradual, and described with such an accuracy that made me want to put the book down and stop reading. To breathe. And exhale my frustration because Clemency was too passive and Christian so ridiculous in his dreams that I couldn’t care less about his childish but destructive machinations.

The pun is easy, but it’s been a harrowing book for this reader. I’ll recommend it for its excellent style, the quality of its execution but you need to be in the mood for twisted relationships before immersing yourself in such a difficult tale.

I very highly recommend Guy’s excellent review of The Catherine Wheel.

This is another contribution to the Australian Women Writer challenge.

20 Books of Summer #3: Blood by Tony Birch – Indigenous Literature Week

Blood by Tony Birch (2011) French title : Du même sang. Translated by Antoine Bargel.

Tony Birch is an Australian Indigenous writer. His debut novel Blood is my third 20 Books of Summer billet and my contribution to Lisa’s Indigenous Literature Week. Lisa hosts this event to help readers discover Indigenous Literature, mostly from Australia and New Zealand. If you want to know more, here’s her post that describes the event and gives book recommendations.

Tony Birch is an Australian Indigenous writer. His debut novel Blood is my third 20 Books of Summer billet and my contribution to Lisa’s Indigenous Literature Week. Lisa hosts this event to help readers discover Indigenous Literature, mostly from Australia and New Zealand. If you want to know more, here’s her post that describes the event and gives book recommendations.

In Blood, Tony Birch introduces us to Jesse and Rachel who live with their useless mother, Gwen. She works where and when she can and she’s constantly attracted to bad boys with criminal streaks and has no motherly instinct.

In Blood, Tony Birch introduces us to Jesse and Rachel who live with their useless mother, Gwen. She works where and when she can and she’s constantly attracted to bad boys with criminal streaks and has no motherly instinct.

Jesse (13) and Rachel (8) almost never go to school. They move too much, living in abandoned farmhouses, in trailers, in shitty flats. Their mother leaves them on their own and the telly is their baby-sitter. They watch a lot of crime shows and films they’re too young to see. Gwen shows no real affection to her children. She’s always on the run.

The children know nothing about a normal life and a normal childhood. They stick together and their deepest fear is to be picked up by social services and to be sent to different foster homes. Jesse feels responsible for his sister, they made a blood pact to always help each other. Gwen is the major source of their issues.

We’d always been on the move, shifting from one place to another, usually because she’d done the dirty on someone, or she was chasing some fella she’d fallen for. And when Gwen fell for a bloke, she had to have him.

Once she shacks up with Jon, an ex-convict. Due to his past, he can’t find a job, stays home and starts to take care of the house and the kids. He’s determined to stay on the wagon and to turn his back to his former life. He sticks to it, cooks, cleans up the house, takes the children to school. They start to have a routine but this life becomes too homely for Gwen, Jon lost his edge and she kicks him out. The children lose a caring adult and are back to square one.

Gwen leaves them behind at her estranged father’s house. Jesse and Rachel have never met him and the improbable trio finds their way together. Stability is around the corner when Gwen shows up again and takes the kids away. Now she’s with Ray and this one is a real criminal. Jesse quickly realises that this man is very dangerous. He starts thinking about running away with Rachel and his hatred for his mother grows.

We know from the beginning that something terrible has happened. Jesse, the only narrator in the book, rings true. He takes us through his life up to the present. The story is suspenseful, breathtaking and heartbreaking. I was hooked from the first pages, mentally cheering the children, dreading for their future and cursing Gwen’s idiotic and shameful behaviour. It’s bleak but Jesse never gives up.

It sounds like American Darling by Gabriel Tallent. I rooted for Jesse and Rachel like I did for Tallent’s Turtle. I wish that Turtle and Jesse could meet, bond and share their mad survival skills. Both Tallent and Birch are gifted storytellers, embarking us on a journey in these kids’ lives. Blood isn’t as emotionally scarring as American Darling but it still made me angry on behalf of Jesse and Rachel.

Blood is on this thin line between literary fiction and crime fiction. (Gabriel Tallent was invited to Quais du Polar, btw.) We see children put on the path of violent criminals by their worthless mother. We wonder where social services are and how children can live under the radar like this. No institution worries when they don’t come back to school. No social worker ever shows up at their house. The world of adults constantly fails them, up to the point that Jesse and Rachel take matters in their own hands.

Blood is a compelling read that will stay with me and I highly recommend it. Many thanks to Lisa for reviewing books by Tony Birch. I knew of him when I visited the bookshop Readings in Melbourne and Blood was among the books I brought back to France.

Sisters by Ada Cambridge – a bleak and cynical vision of marriage

Sisters by Ada Cambridge (1904) Not available in French.

After reading The Three Miss Kings and A Humble Enterprise, I was ready for another feel-good novel by Ada Cambridge and randomly picked Sisters in my omnibus edition of Cambridge’s work. Forget about feel-good and fluffy novels, this one is bitter when the others are optimistic.

After reading The Three Miss Kings and A Humble Enterprise, I was ready for another feel-good novel by Ada Cambridge and randomly picked Sisters in my omnibus edition of Cambridge’s work. Forget about feel-good and fluffy novels, this one is bitter when the others are optimistic.

The book opens on sailor Guthrie Carey, who is on leave and taking his young wife Lily and their baby to their new house. They have to sail there and Lily dies during the crossing. He leaves the baby with a temporary nanny and comes back several months later to find a more stable home for his son. He doesn’t want to get married again, which rules out an easy way to find a new mother to his son.

This is when he gets acquainted with the Urquharts and the Pennycuicks, families who have been friends for a long time and live on neighbouring stations. Strong ties bind the two families and through the Urquhart, Guthrie and the reader meet with the four Pennycuick sisters.

The oldest, Deborah, is beautiful, in her twenties and everyone expects her to marry the local aristocracy, Mr Claud Dalzell. Deborah is lively, slightly self-centred and has a high opinion of her rank in the community. She’s the queen of her little world, boys and men are at her feet. Claud Dalzell, her godfather who’s old enough to be her father, Jim Urquhart and even Carey: all fall for her.

The second sister, Mary, is too plain to get married. She turns her affection on other people’s babies and takes care of the household.

The third sister, Rose, is pretty but not as beautiful as Deborah. Frances, the youngest, is still a child when the book opens but she promises to be even lovelier than Deborah.

Sisters tells the fate of the four sisters while Guthrie Carey appears on and off in the book, like a deus ex machina that throws their lives off balance and makes them go on a spin.

Ada Cambridge weaves a story with the underlying idea that love and marriage are not compatible. Love doesn’t survive the quotidian and people you love shouldn’t be the ones you marry since you should want different qualities in a spouse than in a lover. And also, loves remains beautiful when it stays an idea and doesn’t turn into a real relationship.

Ada Cambridge weaves a story with the underlying idea that love and marriage are not compatible. Love doesn’t survive the quotidian and people you love shouldn’t be the ones you marry since you should want different qualities in a spouse than in a lover. And also, loves remains beautiful when it stays an idea and doesn’t turn into a real relationship.

In Sisters, Ada Cambridge also shows that pride, prejudices and class conscience make people miserable. Deborah is only the daughter of a rich landowner. She’s the aristocracy in her neck of the woods. She’s very attached to her status and would never marry below her rank or what she believes her rank is. She behaves as if she were a princess.

Cambridge points out that, even in on a station where these people started from scratch, they managed to recreate a hierarchy, like in the old world. In Deborah’s eyes, trade is degrading and none of the Pennycuick sisters should marry a tradesman.

As the oldest daughter, she’s in charge of her sisters when her father dies and she’s not fit for it. Her pride will not allow her to make the sacrifices they should do.

She should have managed better with the resources at her disposal than to bring herself to such a pass, and that so soon; either Mary or Rose would certainly have done so in her place. But Nature had not made her or Frances—whose rapacities had been one cause of the financial breakdown—for the role of domestic economists; they had been dowered with their lovely faces for other purposes.

She was supposed to marry a rich man, and that’s all the preparation she had to face life.

In Sisters, men are all flawed. The pastor is a moocher, a greedy man and his temper is not fit for religious duties. Mr Pennycuick is weak, like Mr Bennet. Mr Thornycroft, Deborah’s godfather, lusts after her “ever since she was a kiddie” Eew! Claud Dalzell is a cad. Guthrie Carey falls in and out of love easily and doesn’t want to get married again. The only two decent men are the ones who work to make a living, Jim Urquhart who manages the station and Paul Breen, a draper who will marry one of the sisters, against her family’s will.

I won’t tell much about the plot, to avoid spoilers but the sisters’ lives are dictated by their marital choices. And Cambridge’s conclusion is that:

He did not know what a highly favoured mortal he really was, in that his beautiful love-story was never to be spoiled by a happy ending.

Wow.

I still wonder what she wanted to prove in her novel and why it’s so bitter compared to the others. She was a pastor’s wife and she spent her life in various parishes. Is Sisters the bleak offspring of her observations of married life?

Did she want to point out that men make women’s lives more difficult and that their hard work never has the recognition it deserves?

Mrs Urquhart and Mrs Pennycuick, plain, brave, working women of the rough old times, wives of high-born husbands, incapable of companioning them as they companioned each other, had been great friends. On them had devolved the drudgery of the pioneer home-making without its romance; they had had, year in, year out, the task of ‘shepherding’ two headstrong and unthrifty men, who neither owned their help nor thanked them for it—the inglorious life-work of so many obscure women—and had strengthened each other’s hands and hearts that had had so little other support.

Sisters has a feminist vibe but I found Deborah insufferable. Mary’s lack of confidence was her Achille’s heel. Rose was the most sensible one and Frances, frivolous and vain deserved her fate.

For this reader, it’s always interesting to catch glimpses of everyday life in the 19thC. If you tend to forget you’re reading an Australian book, Cambridge reminds you of it with scorching hot Februaries and by comparing something to an opossum.

Brona has read it too and her review is here.

This is another contribution to Australian Women Writer Challenge

A Humble Enterprise by Ada Cambridge – Melbourne, tea cups and romance

A Humble Entreprise by Ada Cambridge. (1896) Not available in French.

I decided to sign up for Australian Women Writer Challenge again. I had joined this literary event in 2018 and all my Australian readings are in here. AWW (#AWW2020) is hosted by Australian bloggers and its rules are described on their website.

I decided to sign up for Australian Women Writer Challenge again. I had joined this literary event in 2018 and all my Australian readings are in here. AWW (#AWW2020) is hosted by Australian bloggers and its rules are described on their website.

The idea is to read four, six, ten or more books written by Australian women writers. I’ve already read four, so I’m joining the party now. The first ones are two books by Catherine Helen Spence, her novel Mr Hogarth’s Will and her Autobiography.

I had A Humble Entreprise by Ada Cambridge on the TBR because it was included in my omnibus collection of books by Cambridge that I acquired when I read The Three Miss Kings.

It also includes Sisters, A Mere Chance, Materfamilias, The Retrospect and her memoirs Thirty Years in Australia. I’ve read Sisters (upcoming billet). Among the ones I still have on the TBR, which one would you recommend?

A Humble Entreprise doesn’t seem to be one of Cambridge’s most famous books, it’s not even listed on her Wikipedia page.

A Humble Entreprise opens with a familiar scene of 19thC novels: Joseph Liddon, a dutiful clerk at the Churchills’ offices and dies in a tram accident, leaving his wife and his three grown-up children without an income.

A Humble Entreprise opens with a familiar scene of 19thC novels: Joseph Liddon, a dutiful clerk at the Churchills’ offices and dies in a tram accident, leaving his wife and his three grown-up children without an income.

His young son is hired as a clerk in the same office as his father but he can’t support the whole family with his entry-level wages. The eldest daughter, Jenny, comes with a plan: she convinces her mother and sister to open a tea shop in Little Collins Street, Melbourne. To keep the running of the shop simple and efficient, they decide to serve tea, coffee and scones, since Mrs Liddon excels at baking them.

She puts an ad in the paper to advertise the place and Mr Churchill, her father’s former employer, stumble upon it. He remembers about the late Mr Liddon and also that his family declined any financial help from the firm. He’s impressed by their entrepreneurship and their willingness to support themselves with their tea shop.

He decides to visit the place and endorse it. He asks his wife and daughter to have tea there on their next shopping trip to Melbourne and to promote the shop to their lady friends.

Soon, thanks to Jenny’s sound management of their money and Mrs Churchill’s patronage, the place is successful.

Meanwhile, at the Churchill mansion, the family prepares themselves to the return of Mr Churchill’s eldest son, Anthony, from his trip in Europe. His stepmother is particularly happy to see him again, she who hoped to marry him but eventually married his father. She’s still romantically attracted to her stepson, which brings a certain twist to the story.

Meanwhile, at the Churchill mansion, the family prepares themselves to the return of Mr Churchill’s eldest son, Anthony, from his trip in Europe. His stepmother is particularly happy to see him again, she who hoped to marry him but eventually married his father. She’s still romantically attracted to her stepson, which brings a certain twist to the story.

Anthony is thirty-five, still single and thinks it’s time to settle down. If only he could find the right wife. He has played the field enough and knows he doesn’t want a frivolous wife who only cares about clothes and parties. He wants an industrious, caring wife, one who’ll want to take care of their children and not let them too much in the care of nannies.

Guess what happens when he meets hard-working, no-nonsense and entrepreneurial Jenny?

A Humble Entreprise is written for a readership of young girls. Ada Cambridge uses this light and fluffy romance to give advice about love and marriage. There are several passages in which Anthony muses over the qualities he wants in his future wife. Pretty doesn’t come first, he’s more looking for companionship. Ada Cambridge addresses directly to her readers:

And, my dear girls—to whom this modest tale is more particularly addressed—I am credibly informed that quite a large number of men are inclined to matrimony or otherwise by considerations of the same kind. You don’t think so, when you are at play together in the ball-room and on the tennis-ground, and you fancy it is your “day out,” so to speak; but they tell me in confidence that it is the fact. They adore your pretty face and your pretty frocks; they are immensely exhilarated by your sprightly banter and sentimental overtures; they absolutely revel in the pastime of making love, and will go miles and miles for the chance of it; but when it comes to thinking of a home and family, the vital circumstances of life for its entire remaining term, why, they really are not the heedless idiots that they appear—at any rate, not all of them.

Something Jane Austen says in one sentence in Emma, “Men of sense, whatever you may choose to say, do not want silly wives.”

Of course, her views on marriage are in accordance with the mores of her time but she still advocates equality in the personal relationship. She sees marriage as a loving partnership and she clearly wants to teach her readers that beauty evaporates with time and that a good character with adequate skills lasts longer. They should work on useful skills instead of entertaining ones.

I wonder why she didn’t go further and explain to her female readers what they should look for in a husband. After all, women of sense do not want a silly husband either. Drunkards, gamblers, idlers, spendthrifts, cheaters and quick-tempered men should raise warning flags as well. Perhaps she didn’t go there because girls didn’t have the luxury to be picky and could only hope for the best.

A Humble Entreprise is a fluffy novella I’ve read in one sitting, which was exactly what I was looking for. I wanted to read a feel-good novella and it filled the bill. Cambridge writes in a light tone and has a good sense of humour, as you can see in her description of the Churchills going out to downtown Melbourne:

Half an hour later her husband and stepdaughter, two highly-finished, perfectly-tailored figures, sober and stately, severely unpretentious, yet breathing wealth and consequence at every point, set forth together through spacious gardens to the road and the tram—which appeared to the minute, as it always does for men of the Churchill stamp, who are never too soon or too late for anything.

As always, because I’m curious about everyday life in other countries and previous centuries, I enjoyed reading about Melbourne in the 19thC.

Recommended to readers who enjoy 19thC literature and are not allergic to romance.

PS: About the cover. I really don’t understand where this cover comes from. It’s miles away from the atmosphere of the book, as far from it as Nana is from Emma. The second picture is more accurate, you can imagine Jenny running the tea shop while her mother bakes the scones and her sister holds the cash register.

An Autobiography by Catherine Helen Spence – Australia in the 19thC

An Autobiography by Catherine Helen Spence. (1910) Not available in French.

On October 31, 1905, I celebrated my eightieth birthday. Twelve months earlier, writing to a friend, I said:—”I entered my eightieth year on Monday, and I enjoy life as much as I did at 18; indeed, in many respects I enjoy it more.”

Catherine Helen Spence (1825-1910) was a Scottish-born Australian writer, journalist, social worker and political militant. After reading her novel Mr Hogarth’s Will (1865), a novel I described as Austenian, feminist and progressist, I wanted to know more about the woman who wrote it. So, when I noticed on Goodreads that she had written her autobiography, I decided to read it. EBooks are blessings, I don’t know how I could have put my hands on such a book here in France without an easy download of this free eBook copy.

Catherine Helen Spence (1825-1910) was a Scottish-born Australian writer, journalist, social worker and political militant. After reading her novel Mr Hogarth’s Will (1865), a novel I described as Austenian, feminist and progressist, I wanted to know more about the woman who wrote it. So, when I noticed on Goodreads that she had written her autobiography, I decided to read it. EBooks are blessings, I don’t know how I could have put my hands on such a book here in France without an easy download of this free eBook copy.

CH Spence was born in Melrose, Scotland in 1825, in a family of eight. Her father was a banker and a lawyer. In 1839, after her father lost the family fortune, they emigrated to Australia and settled in Adelaide (South Australia). She belonged to a progressive family and benefited from a solid education. Her grandfather experimented with new agricultural methods. He left his farm in the hands of his daughter while he was pursuing other business ventures. In her family, women were part of the family business and not confined to domestic duties.

The capacity for business of my Aunt Margaret, the wit and charm of my brilliant Aunt Mary, and the sound judgment and accurate memory of my own dear mother, showed me early that women were fit to share in the work of this world, and that to make the world pleasant for men was not their only mission.

Her family was very religious (I didn’t understand what religious current it was) and it weighed on her vision of life. She says:

I was 30 years old before the dark veil of religious despondency was completely lifted from my soul, and by that time I felt myself booked for a single life. People married young if they married at all in those days. The single aunts put on caps at 30 as a sort of signal that they accepted their fate; and, although I did not do so, I felt a good deal the same.

She became Unitarian after settling in Australia and never married. From what she writes, I don’t think it was a real issue for her. She had the examples of two very active single aunts with full lives and made a lot of her own. She wrote books, did a lot of social work and was a strong advocate of effective voting. She also raised several orphaned children.

CH Spence writes about her literary career and the difficulty to have one when living in Australia, so far from London. I enjoyed the passages about Mr Hogarth’s Will and her experience as a writer. There are interesting passages about how much she earnt when she sold her novels and how precarious was her manuscripts’ journey to London. I loved her offhanded comment about classics

With all honour to the classical authors, there are two things in which they were deficient—the spirit of broad humanity and the sense of humour.

She knew French and could read book in the original:

It was also from Mrs. Barr Smith that I got so many of the works of Alphonse Daudet in French, which enabled me to give a rejoinder to Marcus Clark’s assertion that Balzac was a French Dickens.

Cheeky me wonders: why wouldn’t Dickens be an English Balzac? After all Father Goriot was published before Oliver Twist.

Besides literature and journalism, Spence explains her social work to improve the lives of women and children in South Australia. With Emily Clark they founded and promoted a system to take children out of destitute asylums and have them raised in approved families. I guess we call it foster care nowadays.

She also fought for a change of the voting system and advocated the Thomas Hare scheme. This is exposed in Mr Hogarth’s Will too and I confess that I didn’t understand the details of the scheme or the voting system in place at her time. The crux of the matter was to change from the current system that was not truly representative of the population to an enlarged pool of voters. Another battle was to obtain the secret ballot. As a feminist, she also petitioned for woman suffrage but thought that it was useless until effective voting was in place.

CH Spence travelled to England and Scotland, visiting the family. She also visited France and Italy. She went to the USA in 1893. She toured the country as a feminist speaker and mad a lot of public interventions. She also visited the Chicago World’s Fair. Imagine that she may have crossed the path of Marie Grandin, a Parisian lady who was at the fair too and wrote about it.

Spence’s autobiography lets the reader hear her voice, the voice of a caring, intelligent and energetic woman. She had strong beliefs and values and put her heart in the causes she chose to advocate. She fought all her life for effective voting. She was still on the board of various social services when she was in her seventies.

I’m glad I read Spence’s autobiography because there were a lot of interesting information in it but it’s not exactly a smooth read. Her prose is a bit heavy and sounds more like an account than a story. She mentions many people that didn’t mean anything to me. They may be famous Australians but as a French reader, it only slowed my reading and it became tedious at times. It feels like she was writing for her contemporary readership and not for posterity. It’s her legacy, an homage to her family, her friends and partners in all her social and political endeavours.

It is also a valuable account of Australia in the 19th century, especially South Australia and Melbourne. However, there is not a word about indigenous people. They don’t exist, it’s like Australia was a desert island at the disposal of colonizers.

My favourite parts were about literature, her comments on writing and characterization, the origin of her novels and her literary interests. I leave you with a last quote for the road, as I know there are many Austen fans out there. 🙂

About this time I read and appreciated Jane Austen’s novels—those exquisite miniatures, which no doubt her contemporaries identified without much interest. Her circle was as narrow as mine—indeed, narrower. She was the daughter of a clergyman in the country. She represented well-to-do grownup people, and them alone. The humour of servants, the sallies of children, the machinations of villains, the tricks of rascals, are not on her canvas; but she differentiated among equals with a firm hand, and with a constant ripple of amusement. The life I led had more breadth and wider interests. The life of Miss Austen’s heroines, though delightful to read about, would have been deadly dull to endure. So great a charm have Jane Austen’s books had for me that I have made a practice of reading them through regularly once a year.

Update on April 26, 2020. I’ve decided to join the Australian Women Writer Challenge for 2020. This is my first contribution.

QDP Days #1 : Kingdom of the Strong by Tony Cavanaugh – Visit Melbourne and its police department

Kingdom of the Strong by Tony Cavanaugh (2015) French title: L’affaire Isobel Vine Translated by Fabrice Pointeau.

Kingdom of the Strong by Tony Cavanaugh (2015) French title: L’affaire Isobel Vine Translated by Fabrice Pointeau.

This is Day 1 of Marina’s and my Quais du Polar. Our beloved festival has been cancelled and we decided to post a billet about a book by an author invited to the festival. Marina’s first review is here. As far as I know, we have three other participants: Lizzy, Andrew and Guy. And maybe Max. I remind you that Pat, at South of Paris Books, read and reviewed the books short-listed for the Quais du Polar prize. The winner will be announced online today.

The festival has organised some online activities, go check them here. Here’s the program for April 3rd, the one for April 4th, and the one for April 5th. Now, let’s go back to Kingdom of the Strong by Tony Cavanaugh, who was invited to Quais du Polar in 2019, the year he signed my copy of his book. It seems a fitting book to illustrate Quais du Polar, Cavanaugh even mentions Lyon and its famous Edmond Locard, who was a pioneer of CSI. (more of that in an upcoming billet)

Kingdom of the Strong is an excellent cold-case crime fiction set in Melbourne. It won the Prix du Meilleur Polar awarded by readers of the publisher Points in France.

Kingdom of the Strong is an excellent cold-case crime fiction set in Melbourne. It won the Prix du Meilleur Polar awarded by readers of the publisher Points in France.

Burned out, Darian Richards resigned from the Melbourne police force four years ago and settled in an isolated cabin in Queensland. To Australian standards, it sounds like leaving the heart of civilisation to live as a recluse in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, only with warmer weather. Poor Darian tries his hand at fishing but doesn’t have the skills of a Jim Harrison character.

So when his former boss and mentor, Copeland Walsh comes to take him out of retirement to work on twenty-five-year-old cold case, the death of Isobel Vine, he has mixed feelings. In appearances, Darian has no wish to jump back into action, in Melbourne or anywhere else but he cannot refuse anything to Walsh, a sort of father figure to him. And, burned out or not, he misses the job.

Copeland was offering more than a job. I’d been trying to fight it but having a hard time. I was remembering the buzz and the thrill of an incoming murder announcement. We lived for murder. It was exciting. In Victoria we’d have about a hundred a year, but we always wanted more. Give me two hundred, three hundred, give me a city of killings. The swirl of the eighth floor, the crews working Homicide, the buzz and the thrill, the oxygen that gets us moving. Eventually, over time, I was poisoned and burned out, unable to break free of the victims and their wraith-like murmurs of anguish fingering out like tentacles, reaching into my increasingly vodka-soaked mind as I kept searching for the very few killers, most notably The Train Rider, who slipped the net, stayed in the shadows, killing again and again or maybe retiring after one or two successful shots at it, leaving behind the plaintive sounds of the victims, calling for justice. Or calling out for me, at least, the guy who wanted to be perfect, Mr Hundred-Per-Cent, that’s how it seemed. I couldn’t deny, not after seeing the boss and hearing the war stories, that old feeling of camaraderie within the ranks of the crews of the eighth. The idea of going back to HQ, to solve a twenty-five-year-old killing, was giving me flutters of excitement.

Against his better judgement, he goes back to Melbourne, and demands his former partners Maria and Isosceles as a team. They start investigating Isobel’s death.

Isobel was in high school and involved with her English teacher, Brian Dunn. She had spent a year in Bolivia as an exchange student and upon Brian’s request had brought a “present from a friend”, drugs. The customs caught her at the Melbourne airport and the police was after her to get the names of her contacts.

Isobel was found dead, hung up with a man tie at her bedroom door, naked. The police concluded it was suicide, a sexual game with a deadly outcome. The night she died, there was a party at her flat and four young cops were among the guests. One of them, Nick Racine is now a serious contender for the position of Police Commissioner in Melbourne. The Premier of Victoria wants to make sure they endorse someone with a clean past.

Darian is in charge of re-opening the Isobel Vine investigation with the purpose to prove once for all, that Nick Racine has nothing to do with her death and that his nomination as Police Commissioner is possible.

They start digging and poking around everyone’s past. They meet with Isobel’s boyfriend, her teacher and the guests of that last fateful party. They stir up bad memories, things that people would rather leave buried now that they have moved on. They do their best to piece together Isobel’s life and see what happened to her.

Tony Cavanaugh is a screenwriter and his novel benefits from it. It’s very cinematographic, it’s fast paced, with a lot of twists and turns. Sometimes, I thought that one or two plot devices were a bit farfetched and now I wish I could ask Tony Cavanaugh if he invented them or if he read about it in newspapers as sometimes reality surpasses fiction.

The narration alternates between the past and the present, letting the reader peek into Isobel’s life. Cavanaugh uses an omniscient narrator for all the characters except Darian. He speaks at the first person. The cast of characters was well drawn and Darian and Maria make a great pair.

The narration alternates between the past and the present, letting the reader peek into Isobel’s life. Cavanaugh uses an omniscient narrator for all the characters except Darian. He speaks at the first person. The cast of characters was well drawn and Darian and Maria make a great pair.

He’s like a lone wolf PI, responding to his own moral code and said moral code is not always in line with legality. He’s a man scarred by his years in the police force, to the point that every street in Melbourne reminds him of a case. It spoils his pleasure of strolling in the city. He only sees the ghost of investigations past. You see that both the French and English covers show a lonely PI with a gun and the Melbourne skyline. I prefer the English cover.

Maria is a spitfire and her boyfriend used to be a big shot in the Melbourne crime community. It’s at odds with her job and she’s always afraid that his former life is not completely over and that his criminal endeavours put stains on her career in the police force. She and Darian make a great team. Helped by Isosceles’s uncanny ability to unearth information about people, they dive into this investigation head on and don’t hesitate to ruffle feathers in the process.

Cavanaugh take us in Melbourne’s back-alleys, in the corridors of the police force where well-established cops feel that they now are on a hot seat. Will they get out of it unscathed? Will they manage to find out what happened to Isobel, twenty-five years ago?

Read the book and find out. It’s an entertaining read, one that will virtually take you out of lockdown. It will take your mind off epidemic thoughts and wash away the virus of anxiety that eats at us, despite our best efforts. Recommended.

A little word about French stuff in this book. I love noting them down.

I mentioned Edmond Locard earlier but several other odd references to French things pop in Cavanaugh’s novel and it was unexpected.

Maria listens to Les Négresses Vertes.

There’s a funny explanation of Voilà! I paraphrase since I have the book in French translation: Cavanaugh says it seems to mean anything from take this to the cat is dead. Well observed, I’d say.

And then when the characters go to a -stuffy- French restaurant in Melbourne, the French waiter is named Jean-Paul. What is it with Australian writers and the name Jean-Paul? Is there an Australian reader out there who can spot the French textbook with a character named Jean-Paul? There must be one. I have no intention to write a book, but I promise that if I ever change my mind, I won’t name the British characters and their dog, Brian, Jenny and Cheeky.

Mr Hogarth’s Will by Catherine Helen Spence – Austenian, feminist and progressist

Mr Hogarth’s Will by Catherine Helen Spence (1865) Not available in French

According to Wikipedia, Miles Franklin called Catherine Helen Spence (1825-1910), the Greatest Australian Woman. And after reading her biography, I can understand why. Born in Scotland, she emigrated to Australia when she was 14, after her family lost their fortune.

According to Wikipedia, Miles Franklin called Catherine Helen Spence (1825-1910), the Greatest Australian Woman. And after reading her biography, I can understand why. Born in Scotland, she emigrated to Australia when she was 14, after her family lost their fortune.

She became a journalist and a writer. She was the first woman to compete in a political election in Adelaide. She was a social activist and worked to improve the quotidian of children living in institutions. She never married but raised orphaned children. Her plate on her birth house in Melrose, Scotland, says it all.

Mr Hogarth’s Will is her most famous novel. When the book opens, we’re in a solicitor’s office in Scotland. Mr Hogarth, a bachelor who raised his late sister’s daughters, Jane and Elsie, has just passed away. He was a gentleman with an estate in Scotland, not very far from Edinburg. He raised the girls as if they were boys, not because he’d wished they’re were boys but because he thought that a boy’s education was a lot more useful in life than a woman’s and that society shouldn’t waste half of its brain power.

Mr Hogarth’s Will is her most famous novel. When the book opens, we’re in a solicitor’s office in Scotland. Mr Hogarth, a bachelor who raised his late sister’s daughters, Jane and Elsie, has just passed away. He was a gentleman with an estate in Scotland, not very far from Edinburg. He raised the girls as if they were boys, not because he’d wished they’re were boys but because he thought that a boy’s education was a lot more useful in life than a woman’s and that society shouldn’t waste half of its brain power.

When the solicitor unveils the stipulations of Mr Hogarth’s will, everyone is in shock. Jane and Elsie are left with almost nothing, because their uncle wanted them to use their skills to provide for themselves. He was certain that their education was enough to help them find a well-paid job.

His fortune and his estate go to his son, Francis Hogarth, a man in his early thirties that nobody has ever heard of. Mr Hogarth got secretly married in his youth and provided for his son and made sure that he became a sensible adult. Francis had been working as a bank clerk for 18 years when his father died. The will stipulates that Francis cannot help his cousins and cannot marry one of them, unless his inheritance goes to charities.

That’s the setting. What will Jane, Elsie and Francis become after this twist of fate? I’m not going to give away too much of the plot because it’s such a pleasure to follow Jane, Elsie and Francis in their endeavors.

Spence put elements from her own experience in the book and uses it to push her social and political ideas. The girls go and live with a former launderess Peggy Walker. She used to work for Mr Hogarth and now raises her sister’s children. She spent several years in a station in Australia and opens Jane and Elsie to the possibilities offered by life in the colonies. She’s a window to Australia.

Francis Hogarth is a good man, who is embarrassed by all the money he inherited. He would like to help his cousins but he can’t. He and Jane develop a good relationship, as he enjoys her conversation and her intelligence. He had to earn a living before getting all his money, and knows the value of hard work and well-earned money. He will experiment new things in his estate, to better the lives of the labourers on his land.

Elsie is prettier than Jane, more feminine too. She’s more likely to make an advantageous marriage. In appearance, she’s more fragile than Jane and relies on her older sister. She’l make a living as a milliner.

Of course, Jane can’t find a job in Edinburg because nobody wants to hire a woman even if she has the skills to be a bank clerk like Francis. Finding a job as a governess seems tricky since she can’t play the piano, embroider or paint. She eventually finds one with the Philipps, a Scottish family who got rich in Australia and is now back in the old country and lives in London.

Spence mixes a set of characters who have lived in Scotland all their lives and some who have lived in Scotland and in Australia. It allows her to compare the two ways of life and advertise life in the colonies. Through her characters, she discusses a lot of topics but I think that the most important point she’s making are that people should be judged according to their own value and accomplishments and not according to their birth.

Indeed, Jane and Elsie never look down on people who were not born in their social class and don’t hesitate to live with Peggy Walker or ask Miss Thomson’s for advice. They respect people who have a good work ethic, common sense and do their best with the cards they were given. And, according to Spence, Australia offers that kind of possibilities.

Spencer also insists on education as a mean to develop one’s skills and reach one’s potential. What’s the use of an education centered on arts and crafts? It’s a beautiful companion to other skills –Francis Hogarth is a well-read man—but how useful is it to find work? Why not help poor but capable young men to better themselves through a good education that gives them access to better paid professions? That’s what Jane does with Tom, one of Peggy Walker’s nephews. The social canvas is brand new in Australia, Spence says that capable people have better chances at succeeding there than in Scotland.

Reminder: this book was published in 1865. She was such a modern thinker.