Archive

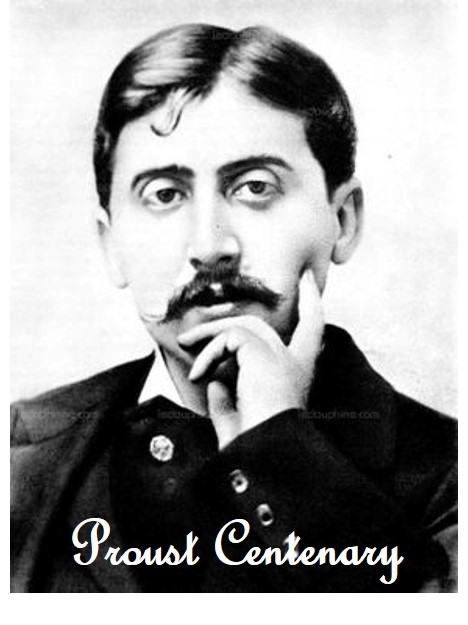

Literary Escapade: the Proust Exhibition at the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris.

For the centenary of Proust’s death, the Bibliothèque nationale de France (Bnf), the French equivalent of the Library of Congress, curates an exhibition entitled Marcel Proust – La fabrique de l’œuvre. It means Marcel Proust, the making of his work.

In French, A la Recherche du temps perdu, In Search of Lost Time in English, is nicknamed La Recherche and I’ll use that expression in my billet as it conveys a familiarity and a fondness for it.

This exhibition takes us through Proust’s creative process. For each book of we can see how Proust wrote and reviewed his work and, for the volumes published after his death, how his work came to us.

The exhibition shows 370 pieces from the Proust fund at the BnF. Marcel Proust had kept all of his manuscripts and his brother Robert inherited them when Marcel died. Suzy Mante Proust, Robert’s daughter, donated the manuscripts to the BnF in 1962.

Therefore, the BnF has almost all of Proust’s manuscripts from his school essays to La Recherche. They have 26 volumes of proofs and boards, 23 type-written texts, drafts typed by various secretaries, many paperoles, 23 notebooks of edited texts, 75 notebooks of drafts, hundreds of paper sheets, four other notebooks and one diary. That’s a lot of material and here’s a picture of the different sources.

Marcel Proust didn’t write La Recherche from the beginning to the end in a linear fashion. He wrote Swann’s Way and Time Regained at the same time. He wrote episodes of La Recherche here and there and put them in the volumes where he saw fit.

Now, let’s have a tour of the different volumes and I’ll share with you pictures and anecdotes.

Du côté de chez Swann (Swann’s Way). 1913 (self-published) and 1919 (reviewed edition – Gallimard)

Longtemps, je me suis couché de bonne heure is probably one of the most famous incipits of French literature, along with Aujourd’hui, maman est morte, from The Stranger by Albert Camus. The BnF showed the different versions of this incipit until Proust settled on Longtemps, je me suis couché de bonne heure. They did the same about the madeleine, from toast (1907-1909 drafts) to rusk to a madeleine.

It was fascinating to witness Proust’s thought process, the attention to details and have the evidence that the incipit and the key moment of the madeleine were thoroughly forethought. The first version of Swann’s Way was published in 1913 but it was in the making since 1907. It goes against the idea of a Proust who wasted his time in society life and didn’t start working hard until later in life.

The exhibition also features key objects of the books and for Swann’s Way, I was mostly interested in this drawing from a magic lantern telling the story of Geneviève de Brabant.

It’s a story that the young Narrator used to love and this shows us what kids saw in their magic lanterns.

Proust was a master of copy-paste, long before office solutions and computers were invented. This board from Swann’s Way shows how Proust worked.

Fascinating, no? (Or maybe a typist’s nightmare…) Now let’s move on to the Narrator’s adolescence with…

A l’ombre des jeunes filles en fleur (In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower) 1919 – Prix Goncourt

This volume is key as the Narrator gets acquainted with major characters of La Recherche: Robert de Saint-Loup, the group of girls to which Albertine belongs, the painter Elstir, the Baron de Charlus and the Verdurin clan. We’ll follow them all during our literary ride with the Narrator, from Balbec to Paris.

Le côté de Guermantes (The Guermantes Way) 1920-1921 (Published in two volumes)

The Guermantes Way is where the Narrator is of all the parties and in the heart of high society. It’s the turning point of his adult life: the high society isn’t a glamorous fairytale anymore, as the harsh words of the Duc de Guermantes to a dying Swann remind us. He’s about to explore the kingdom of Sodom and Gomorrha through Charlus and Albertine.

Sodome et Gomorrhe – 1921-1922 (Published in two volumes)

The discussion about homosexuality was conceived as soon as 1909. Marcel Proust didn’t know yet where he would include it. The reader understands as soon as the Baron de Charlus is introduced that he’s gay. The Narrator will only see the light when he catches the Baron de Charlus and Jupien.

Homosexuality is also a hot topic as the Narrator suspects that Albertine is a lesbian. He’s aware of lesbian relationships since Balbec when he saw Mlle de Vinteuil and her friend.

Sodom and Gomorrah were the last volumes published under Marcel Proust’s supervision. Marcel Proust changed the structure of La Recherche several times; for example, he toyed with the idea of three volumes for Sodom and Gomorrah.

The last three volumes were published by Gallimard with the help of Robert Proust. Here’s a letter from Gallimard to Robert Proust describing the final division of La Recherche in the current number of volumes.

The Narrator has now feelings for Albertine and their relationship mirrors Swann and Odette relationship.

La Prisonnière (The Captive) –1923

Marcel Proust wanted La Prisonnière to be the third volume of Sodom and Gomorrha and he sent to Gallimard his last review of the typed version of La Prisonnière a few days before he died.

The exhibition shows a report from A. Charmel, the concierge of the 8 bis rue Laurent Pichat where Marcel Proust lived from May 31st to October 1st 1919. This report is about all the cries from the street vendors and the various trades on a typical Parisian Street.

It will become a famous scene in La Prisonnière where the Narrator listens to the noises coming off the street. It’s a vivid passage that brings the reader to the Paris of this time, to all the street vendors and odd jobs that have disappeared now.

Except from 1909 to 1911, Proust wasn’t a solitary man. He had a lot of people around him, helping him. He sent out friends and servants to check certain details and facts and all this was included in his work.

Albertine disparue (The Fugitive). First title La fugitive 1925

Just before he died, Marcel Proust retrieved 250 pages of Albertine disparue, undermining the consistency of the volume. Robert Proust decided to keep these pages after Marcel died. I guess it was the best choice, no one knew how Marcel would have modified his work to straighten the narrative. I’m relieved to know that Marcel Proust thought that something was off in this volume as it’s the one I struggled the most with.

Le Temps retrouvé (Time Regained) – 1927.

In Time Regained, Proust writes about Paris during WWI and here’s a picture of a bombing near the metro St Paul, rue de Rivoli (Night 12-13 April 1918)

It also means that the first version of Time Regained, written before the war started, has been augmented. Marcel Proust added a fascinating picture of Paris during WWI, life behind. He lost friends and acquaintances during the war and he adapted his characters’ fates to the events. He even changed the location of Combray from the West of Paris to the East.

In each room of the exhibition the visitor could see how the novel was finished and got ready for publication: drafts, notebooks, typed sheets, additions through paperoles, phrases crossed and rewritten…All precious testimonies of the making of La Recherche.

This is a major exhibition about Proust. I wasn’t aware of his writing process. I knew about the drafts, adds-on or paperoles and that he sent out Céleste or her husband to check out things.

I didn’t know that he wrote La Recherche in pieces and not in the chronological order. I didn’t know that his books were made of pieces stitched together and that Proust sewed his book together like a couture dressmaker.

I had this image of a Proust writing frantically, knowing his years were counted. It may stem from Time Regained where the Narrator understands late in the game what he has to write. But in Proust’s real life, this epiphany came a lot earlier than I thought and his work is even more astonishing.

We’re talking about a writer who had his masterpiece in mind from the beginning. Given the length, the complexity and the number of characters, his mind was more than a brilliant machine. He knew what he wanted to demonstrate but he didn’t have everything mapped out, or he wouldn’t have changed the structure of the volumes until the end or included historical facts along the way. He had key scenes written and the global idea of what he wanted to pass on about art, life, memory and our journey on this earth.

The key scenes are wonderfully polished because they were written and rewritten, his ability to adapt to real life events roots the novel in French history and this vision of society is also priceless. Proust has the amazing ability to dig deep into people’s inner life without cutting them off real life. He was like that too, having the vivid imagination of an introvert and living the life of a social butterfly.

Extraordinary.

Now, a last picture for the road, this is Marcel Proust’s writing material.

Proust reads and reading Proust

Days of Reading by Marcel Proust (1905) Original French title: Sur la lecture. Suivi de Journées de lecture.

Proust by Samuel Beckett (1931) French title: Proust. Translated by Edith Fournier.

Proust died on November 18th, 1922. The centenary of his death has been celebrated here with books, TV specials, newspapers, podcasts, radio shows, exhibitions and so on. I meant to publish this billet on November 18th but life got in the way.

Days of Reading is a short essay by Proust, where he muses over the pleasure and the experience of reading.

As often, Proust shows his talent for a catching incipit.

| Il n’y a peut-être pas de jours de notre enfance que nous ayons si pleinement vécus que ceux que nous avons cru laisser sans les vivre, ceux que nous avons passés avec un livre préféré. | There are perhaps no days of our childhood that we lived as fully as the days we think we left behind without living at all:the days we spent with a favorite book. Translation by John Sturrock. |

In the subsequent pages, he remembers the glorious hours he spent with books as a child. He wanted to be left alone with his books and not do anything else. I can relate to that.

His thoughts about finishing a book, the fact that we leave the characters on the last page to never “see” them again is relatable too. Who has never reached the end of a book thinking “That’s all? What will become of them now?”. He muses over our relationship with books, our connection to writers and how they lead us to beauty and intelligence. La lecture est une amitié, he says. And yes, reading is a friendship with books, authors and imaginary worlds.

While Proust talks about his love for reading in Days of Reading, Beckett writes about his response to Proust’s masterpiece In Search of Lost Time.

Beckett wrote Proust, his essay about In Search of Lost Time, in 1931, when he was only 25. Time Regained had only been published four years before in 1927. Beckett was an earlier adopter of Proust and it says something about his ability to understand modern literature and spot a breakthrough in literature, even if Proust wasn’t taken so seriously at the time.

Proust is not an academic essay, it’s the brilliant review of a book through the eyes a passionate reader. Beckett shares his experience with reading Proust and displays a deep knowledge of Proust’s work.

He gives very detailed and precise examples – he quotes from memory, a nightmare for the French translator of his essay because she needed to find the actual quotes in French…He shows a profound understanding of what Proust intended to do with his work and he was ahead of his time.

Beckett goes through all of Proust’s favourite themes: the force of habit, the importance of a setting, his fascination for the Guermantes, his passion for art (literature, painting, opera, music, theatre and architecture.) He has valid points about the relationship between Albertine and the Narrator.

And then come thoughts about memory, remembrance and our thought process. He gives his perception of how memories are triggered by sensations.

Proust is an impressive review of Proust’s masterpiece and it’s a tribute to Beckett’s intelligence as much as an ode to Proust. It’s an excellent companion book for any reader of La Recherche, as we have nicknamed In Search of Lost Time in French.

Proust reads and Beckett reads Proust. I missed the actual day of the centenary of Proust’s death but still decided to bake madeleines to celebrate this anniversary.

Time Regained by Marcel Proust – a conclusion and a beginning.

Time Regained by Marcel Proust (1927) Original French title: Le Temps retrouvé.

Time Regained is the last volume of In Search of Lost Time and it was published five years after Proust’s death. We’re lucky that Proust’s brother had them published.

I’ve now finished rereading In Search of Lost Time. It took me several years because I wandered away, lost time and yet always found my way back to it. I never forgot where I left the Narrator and resumed reading as if I had stopped the day before. Proust’s prose and narration is a drizzle, it pervades into your brain and your soul. It goes deep and stays with you on a long-term basis.

I first read Time Regained in my last year of high school. My memories of reading it were of a brilliant conclusion to In Search of Lost Time, the book where everything starts and ends in a coherent way, a volume that made the whole journey worth all the reading time I devoted to Proust.

My memories were accurate, if it even makes sense to apply this adjective to memories after all Proust has written about their fleetingness and inaccuracy. I have twenty-five pages of quotes from Time Regained, all worthy of attention. I’m not qualified to write an essay about Proust, an imperfect summary is all I can hope for.

This last volume has three parts all equally fascinating and for different reasons.

The first part is about Paris during WWI and how things were for Parisians and Proust’s circle. The Narrator is back to Paris after two years in the country, in a nursing home. From a historical standpoint, this part is very interesting. He pictures the political context of the time and the attitude of the various characters of his novel towards the Germans and how they express or broadcast their patriotism. The war time has rearranged the cards in his friends and acquaintances’s position in the world. He unveils what the characters are up to during these difficult times. Who became a journalist. Who is on the front. Who is an army deserter. What women do and what salons have become. Who works for the government. What happened to Combray, Méséglise and a little bridge on the Vivonne river. Who is a spy. How Françoise lives through this.

But people are people and life goes on. Thanks to Charlus, Jupien runs a brothel for homosexuals, which provides for the Baron’s enjoyment of sadomasochism and the Narrator witnesses it all. (Proust used to go to this kind of brothels himself, he even got arrested in one once).

After the Narrator updates us on what happened to several of the characters, he goes to a matinée hosted by the Princesse de Guermantes, the new one, since the prince has remarried.

When he arrives at their mansion, he stumbles upon a paved stone and Venice is brought back to his memory with the same force as Combray with the madeleine. He enters the mansion and has to stay in the library until the musicians whon are currently playing have finished their piece. Then he’s be allowed into the salon. This time in the Guermantes library is a revelation. Several details trigger his memory and his brain and his literary mission downs on him. His artistic pursuit is not a pipedream after all. He now knows what he will write, how he will write it. He’s on a mission.

This second part is a breathtaking explanation of how Proust conceived In Search of Lost Time. He explains his vision of art and what was the starting point of the work we’ve been reading. The conception of his artwork is laid out here, in the book itself, in a brilliant mise en abime. We read about the aim and the blueprints of his literary cathedral. And right there, in this library, he can’t wait to start writing it. Unsurprisingly, his epiphany has something to do with the perception of Time.

But before shutting himself up to write, in a hurry to ensure he has enough time to finish it before he dies, he has to attend the party. And this party is the ultimate place to meet all kind of people from the past. Some are only there through the remembrance of guests as they are dead. Most of the guests have suffered from the assault of Time. They are grey, old, senile, forgetful. The social order is askew or even upside down. And the Narrator observes them with his acute perception, seeing through them and pointing out the changes and the ridicules.

An era is dying. Time has taken his toll and the Narrator is going to bring them back, not in a realistic way but through is perception of them. He will take us from the beginning of the Third Republic to WWI and describe a milieu and an era. There will be political, social and mored matters. There will be no judgment, no question of sin and morality. He will dig into himself and analyze others to show the mechanisms of love, jealousy, grief, habits, imagination and oblivion.

It’ll be a lie. It’ll be non-linear and impressionistic. It’ll be human. It’ll be a masterpiece.

Literary escapade: Marcel Proust on his mother’s side – an exhibition

After the exhibition at the Musée Carnavalet (see my billets here and here), my celebration of the centenary of Proust’s death continues with another Parisian exhibition. Indeed, the Musée d’art et d’histoire du judaïsme set in the Marais quarter currently hosts an exhibition about Proust on his mother’s side.

Proust’s great grandfather, Baruch Weil (1780-1828) directed a porcelain manufactory in Fontainebleau and was the official circumciser of the synagogue Notre-Dame-de-Nazareth in Paris. Nahé, one of his sons, married Adèle Berncastel (1824-1890) they had a daughter, Jeanne.

Jeanne Weil married Adrien Proust, a doctor from Eure-et-Loir who was probably a freemasonry acquaintance of her father.

Combray is on Adrien’s side. Adrien and Jeanne had a civil marriage and decided that their children would be educated as catholic. Nevertheless, Marcel and Robert went to the Lycée Concordet, a Républican high school and not a Catholic school.

So, Adèle Weil is Proust’s grandmother, the one who reads Mme de Sévigné and Saint-Simon in In Search of Lost Time. Jeanne is Proust’s mother. Adèle and Jeanne had a solid education and studied more than most girls of their time who were brought up for marriage and nothing else. (See Balzac and Flaubert) Here are photographs of these two important ladies who raised Marcel into the writer he became.

Marcel Proust was close to the Weil family. His great-uncle Louis lived in Auteuil where Proust used to live when he was a child. The great-uncle Louis is in In Search of Lost Time under Oncle Adolphe. He was rich and had no children: he left his money to his nephew Georges and his niece Jeanne and Marcel inherited part of his fortune after his mother died.

Jeanne Weil was very important in her son’s life. They had a close relationship. It came from the circumstances of his birth (right during the Paris Commune and his poor health. (Marcel almost died of an athma attack when he was ten) Beside her traditional role as a mother, she was the one interested in arts. She traveled with him, helped him translate Ruskin as her English was better than his. Adèle, Jeanne and Marcel were the art lovers while Robert was more into science and sports and closer to his father.

The exhibition aimed at pinpointing the importance of his Jewish roots in Proust’s life and literature. Sometimes I thought the connections were obvious and interesting to explore and sometimes I thought it was a bit farfetched. Let’s start with those.

The exhibition makes a comparison between Proust’s manuscripts and their “paperoles”, additions to the text and transcripts of the Talmud with their peripheral commentaries surrounding the text. See for yourself.

Sure, his “paperoles” and additions to the text exist but any other writer could have done the same, no?

His Jewish family lodgings in Auteuil or in Paris became places in his novel. His stays in Normandy from 1880 to 1914 among the Jewish intelligentsia are in the center of In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower. This is where we hear about the Narrator’s Jewish friend Bloch. It was the opportunity to see a few paintings as illustrations of the atmosphere of the time. I always enjoy impressionist paintings and I love that they give us glimpses of life at the end of the 19th century.

There is also a special display about Esther, Jewish the heroin of The Book of Esther. Jeanne Proust admired this heroin a lot and Sarah Bernhardt (La Berma) performed in the play Esther by Racine. It was also mentioned that Raynaldo Hahn, Proust’s friend and ex-lover accompanied her at the piano.

Then the passage about Charlus’s secret. He’s one of the homosexual characters of In Search of Lost Time. The link between homosexuality and the Jewish community is that both communities had to lay low. It sounds more an excuse to include the major theme of homosexuality in the exhibition than anything else.

I thought that the real themes about Jews in In Search of Lost Time are the Dreyfus Affair and how Proust paints Jewish characters. The Dreyfus Affair is a key topic in Proust’s work. He was on the Dreyfusard side, right from the beginning. He supported Zola and signed a protest. And yet he remained friend with the despicable Léon Daudet, a notorious anti-Semitic writer. (I’m glad that Proust never got to see how his friend turned out in the 1930s until his death)

His work depicts with accuracy the impact of this affair on the social order. He shows how families were torn apart. With light touches here and there, he makes the reader understand how antisemitic the French society was and I can truly say that reading Proust made me understand how Vichy happened. There were antisemitic roots that Vichy watered, grew and exploited.

The two main Jewish characters in Proust’s masterpiece are Charles Swann and Bloch. Swann represents the elegant and cultivated Jew while Bloch embodies the opposite. Proust was sometimes criticized because his Jewish characters seem caricatural while they are only the mirror of the society’s prejudices and not reflecting the author’s opinion.

The exhibition also points out that the Zionist movement rapidly stressed Proust’s Jewishness. It happened right after his death, in the 1920s. His work was quoted in several reviews and his recognition as a Jewish and universal artist was early. This is something I wasn’t aware of.

All in all, it was informative and interesting to think about Proust’s work through his Jewish background. It was the opportunity to visit this museum and see its permanent collections about Jewish history and culture.

Marcel Proust & Paris Exhibition – People and characters

I imagine that a lot of readers of In Search of Lost Time wonder who were the real people behind the main characters of Proust’s masterpiece. The characters are so striking that they stay with you years after you’ve read La Recherche and it’s natural to want to dig out who was who between the Narrator’s life and Marcel’s. It doesn’t help that the Narrator is named Marcel, it blurs the lines between fiction and autobiography.

The Marcel Proust and Paris exhibition that I mentioned in my previous billet showed real life person vs characters.

Odette de Crécy

Odette de Crécy is the courtesan who captures the imagination and the heart of Charles Swann. We meet her in the first volume, Swann’s Way. She’s also the mother of Gilberte, the Narrator’s first love.

Odette de Crécy is modelled after Laure Hayman. She was a courtesan, first the mistress of Proust’s great-uncle Weill, then of his father Adrien. The rumor says the Marcel wanted to take over the family tradition and propositioned her but she rejected him. She had a salon, 4 rue La Pérouse in Paris, where famous writers went. Some dukes too but not their duchesses. She wasn’t too happy to recognize herself in Odette de Crécy, even if Proust always denied that it was her.

Charles Swann

Charles Swann is the key character of Swann’s Way. He was friends with the Narrator’s parents, went to salons in the high society and his love for Odette led him to the bourgeois salon of Madame Verdurin. He was very cultured and refined, his love for Odette was a surprise in the higher circles.

Swann’s real-life counterpart is Charles Haas (1832-1902) He was a star of several salons, including Madame Straus’s. Like Swann, he was Jewish, well-introduced in the world and known for his intelligence, his excellent manners and his broad culture. He was the lover of several famous ladies, like the actress Sarah Bernhardt. (Herself a model for La Berma in La Recherche)

Robert de Saint-Loup

Robert de Saint-Loup is the Narrator’s dear friend. They confide to each other, spend a lot of time together. They have a really close relationship. The Narrator knows about Robert’s liaison with the actress Rachel and Robert knows that the Narrator hides Albertine in his home.

Proust had several friends from his high school days but two dear friends stand out in his life. The first one is Raynaldo Hahn. They were close friends during twenty-eight years, it ended with Proust’s death. Hahn was a musician and a composer. Their relationship started with a liaison that turned into a long-lasting friendship. I’d like to think that there is something of him in Robert de Saint-Loup. The specialists think differently.

Robert de Saint-Loup was modeled after two other friends of Proust: Prince Antoine Bibesco (1878-1951) and Bertrand de Salignac-Fénelon (1878-1914).

A scene in La Recherche, where Robert de Saint Loup goes for the Narrator’s coat when he’s cold in a restaurant has happened in real life between Marcel and Bertrand. Bertrand de Fénelon died in combat in 1914, his body was never found. Proust only learnt about his death in March 1915 and was very distressed by his loss. Specialists think that Fénelon misunderstood Proust’s love for friendship. He died the same year as Agostinelli and the grief has certainly fueled Albertine Gone.

The Baron de Charlus

The Baron de Charlus, brother of the duc de Guermantes is the most famous homosexual character in La Recherche. He’s an art afficionado, appreciated in salons for his artistic tastes. In La Recherche, we will see him in the throes of passion, we will follow him to gay brothels and discover the underground gay Paris. Proust knew it well too.

Everyone agrees to see Robert de Montesquiou (1855-1921) in the Baron de Charlus. Proust and Montesquiou met in Madame Lemaire’s salon. They admired each other greatly and Proust called him “professeur de beauté” (teacher of beauty)

Montesquiou was a dandy, a poet and a novelist. He was the cousin of the comtesse Greffulhe. Like Laure Hayman, he was furious to discover himself as a character in La Recherche. I’ve never heard of him as a writer, even if he wrote eighteen collections of poems, two novels and twenty-two art and literature critics. He was very influencial in Proust’s life, for introducing him in salons and for developing his artistic tastes. He was an early promoter of lots of poets and artists, with an incredible capacity to unearth new talents and adopt new forms of art.

I haven’t read Against Nature by Huysmans, but Montesquiou also inspired the character of des Esseintes.

Madame Verdurin

Madame Verdurin has a salon that grows from bourgeois to high society in the course of La Recherche. She has around her a little clique of writers, musicians, painters and other professions. Madame Verdurin is based upon Madeleine Lemaire.

Proust was a frequent visitor in Madame Lemaire’s salon. He met there several of his close friends or acquaintances, like Raynaldo Hahn or Robert de Montesquiou. Madame Lemaire had a famous salon where numerous artists met. She was a painter herself and illustrated Proust’s first book, Les Plaisirs et les jours, in 1896. Like Madame Verdurin, she was very peremptory in her likes and dislikes and regular visitors of her salon were expected to bow to her judgements.

The duchesse de Guermantes

The duchesse de Guermantes was the Narrator’s ideal. He dreams about her and maneuvers to go to her salon. Being a regular guest at Oriane de Guermantes’s soirees is the highlight of his society life. The enchantment lasts a moment but the Narrator quickly discovers his idol’s flaws and the duchesse de Guermantes turns out to be not so likeable after all. The duchesse de Guermantes was created after the Comtesse Greffulhe, Madame de Chévigné and Madame Straus.

The Comtesse Greffulhe was a star in the Parisian high society at the turning of the 20th century. She was a painter and played the piano. She promoted various artists and loved Wagner, whom Proust adored too.

The Comtesse Geffulhe met Proust in 1893, at a soirée at the princesse de Wagram’s. She was a lot more intelligent than La Recherche lets out. She helped artists but also funded Marie Curie, as she was also interested in science.

Proust met Laure de Sade, future comtesse de Chévigné in 1891. She’s the descendant of the Marquis de Sade and she had a famous musical salon in Paris, 34 rue de Mirosmenil. Like the Narrator with the duchesse de Guermantes, Proust used to watch out for her when she was taking her morning stroll. Proust was fascinated by her and in love with her too. They remained friends during twenty-eight years, until she was hurt when she discovered herself in Madame de Guermantes and refused to read Proust’s novel.

Some say that the duchesse de Guermantes was also inspired by Madame Straus (1849-1926)

She also had a famous salon where artists gathered. Maupassant was a frequent visitor (She’s the main character of his novel Fort comme la mort). Robert de Montesquiou went to her salon too.

This is where Proust met Charles Haas, who will become Swann. In 1898, the Straus move into their new mansion, 108, rue de Miromesnil.

The duc de Guermantes

The duc de Guermantes is a formidable character in La Recherche but he’s not as interesting to the Narrator as his wife Oriane or his brother Charlus. Indeed, he has nothing in common with the Narrator. He cheats on his wife, he’s rude, talks with a booming voice, and is not interested in the arts.

He’s modeled after the comte Greffuhle. He was fabulously rich, cheated on his wife repeatedly and as soon as they were married. He loved hunting, understood nothing to art and disliked his wife’s artistic friendships. Sounds like the duc de Guermantes to me, indeed.

Albertine

And what about Albertine? It is admitted that Albertine was modeled after Alfred Agostinelli (1888-1914) He met Proust in 1907 when he drove him to Normandy. Agostinelli was a chauffeur who became Proust’s secretary. Agostinelli was passionate about aviation and he died in a crash in 1914. Proust was in love with him but his love was unrequited. Now you know where Albertine Gone comes from.

Artists in La Recherche.

Bergotte is THE writer in La Recherche. The Narrator loves his books. Bergotte is a frequent guest at Madame Verdurin’s, which confirms her ability to detect real talents. He seems to have been made of Anatole France and Paul Bourget. Ironically, unlike Maupassant or Zola, they are not a writers that people commonly read today. The irony. Anatole France had national funerals when he died but I think that his books are unreadable today.

Elstir is THE painter of La Recherche. He’s an impressionist based upon Monet, Manet, Renoir, Helleu, Whistler and Boudin. Proust must have met Monet, Manet and Renoir through Mallarmé, who was close to Berthe Morisot’s circle. He’s also a member of Madame Verdurin’s salon.

Vinteuil is THE composer of La Recherche with his sonata. There’s no actual link with a real composer.

La Berma. This actress features in beautiful pages about Phèdre and theatre. It is notorious that Sarah Bernhardt (1844-1923) and Réjane (1856-1920) inspired the character of La Berma.

After writing about all these characters of La Recherche and their real-life inspirations, it strikes me that it was really a small world. The salons were very close, geografically and they all knew each other. How was it to be surrounded with so many great artists? What has become of salons today and what replaced them?

A lot of Proust’s models didn’t like how he portrayed them in his novels. Was he too harsh or didn’t they like that he saw through them so well? I suppose there are some clues in Proust’s abundant correspondence. What they didn’t foresee is that their socialite friend or acquaintance would give them a form of immortality. Truly, all these people would have been long forgotten if Proust hadn’t used them in La Recherche. So, literature gave them their immortality. The only ones who survived through their own merits are the painters who shaped out Elstir and and in a lesser way the writers who inspired Bergotte.

I hope you had fun with me in peaking at what was behind the scenes of La Recherche and read about its who’s who.

PS : Another thought. We must be grateful that Robert Proust was not the same prick as Paul Claudel. Otherwise, you bet that some serious editing about homosexuality would have been done in the volumes published after Marcel’s death. And let’s not think about what could have happened to his correspondence.

Marcel Proust & Paris Exhibition – Proust in Paris

The exhibition Marcel Proust, Un roman parisien at the Musée Carnavalet shows the importance of Paris in Proust’s life and in In Search of Lost Time. (“La Recherche”). It explores Proust’s Paris and the fictional Paris of La Recherche.

Proust has lived in Paris all his life, except for his stays in Illiers-Combray or Cabourg and his travels to Venice. The exhibition traces his family’s origins, the apartments they occupied in Paris and the places they used to spend time in. There are even maps of them!

Proust was born in 1871 in Auteuil, a village incorporated to Paris in 1860 and which is now the wealthy 16th arrondissement. His great-uncle had a country house there and Proust’s parents found shelter there during the Commune. Then they moved to the 8th arrondissement, where Proust would spend all his life. This area of Paris was modeled by the Baron Haussmann: large avenues, trees, not far from the Bois de Boulogne.

Rich bourgeois had mansions built there. In today’s touristic Paris, it’s the Boulevard Haussmann and its famous department stores, the Garnier Opera, the La Madeleine Church, the Saint-Augustin Church. We have to remember that for Proust as a child, everything around him was rather new.

The exhibition shows all the places that were Proust’s quotidian in Paris, so there is nothing about Cabourg or Illiers, translated as Balbec and Combray in his novel.

Proust spent his early childhood in Auteuil. Laure Hayman, a famous cocotte of the time was his great-uncle mistress. Marcel went to play at the Champs Elysées and he had various crushes on girls. His father, Adrien Proust, was a gifted doctor who had a brilliant career fighting for hygiene and against epidemics (cholera). He studied how epidemics spread and how to prevent their spreading. I listened to a series of podcasts about his work and actions during the first lockdown and it was fascinating. Proust’s mother, Jeanne Weill, came from a rich Alsatian-Jewish family of tradesmen. They had stores in Paris. She was the one who shared Marcel’s interest for literature and the arts, and, as the Narrator’s mother, was devastated by her mother’s death.

Proust had his mother’s eyers, no? We can imagine that Proust’s younger brother, Robert, who became a doctor, was closer to their father.

Marcel Proust went to the high school at the Lycée Condorcet. The students there were mostly non-religious bourgeois as the others were in private Catholic schools. Imagine that he had Stéphane Mallarmé as a teacher! They say he was very influential in Proust’s youth. Personally, I find Mallarmé’s poetry unreadable, I tried again after reading Berthe Morisot’s biography. Proust met close friends during his formative years at Condorcet and was an active participant to the high school newspapers and started his first literary work during those years.

Growing up, he met people who introduced him to the high society. I took pictures of all the key people who inspired the characters of La Recherche but that will be in another post. These are the years he spent in salons, translating Ruskin, writing articles for Le Figaro and gathering memories and material for his future masterpiece.

Following the death of his father (1903) and his mother (1905), he had to move to a smaller apartment, still in the same neighborhood.

The exhibition shows what Paris was like for Proust at the time, knowing that he never left the very wealthy 8th arrondissement. Maps showed the places he used to go to, like shops and restaurants. Some still exist, like the bookstore Fontaine and the restaurant Maxim’s. The gay brothel he financed and frequented, the Hôtel Marigny was on the map too. There was a map of the theatres and operas he loved and out of the nineteen places, I counted that only three don’t exist anymore. They may have moved but they are still there and that, in itself, is a tribute to the vibrant Parisian theatre scene. See an illustration with this very contemporary street corner in the 10th arrondissement.

The most surprising thing was Proust’s subscription to the Théâtrophone service. It was a service you could subscribe to in order to listen to live theatre plays and operas over the phone. It started in 1890 and was in operation until 1932, replaced by the radio. Proust loved theatre and operas and he signed up for this service in 1911. He listened to Wagner’s operas and Debussy’s music. We’re talking about the first streaming service for music and theatre here. Isn’t that mind-blowing? Reading a bit about it, I discovered that this service was invented and sold by Clément Ader, who made a fortune out of it and used the money to finance his researches on aviation. From music to planes!

When we think about Proust, we picture the whirlwind of soirées, shows and salons, but Proust wasn’t disconnected from politics: he was a fervent support to Dreyfus and Zola. He followed closely the battles during WWI and stayed in Paris during the whole war. He was interested in the world’s affairs.

Meanwhile, in 1906, he starts writing La Recherche, as if he needed his parents gone to spend some serious time on writing. The first official recognition came with the Goncourt prize for In the Shadows of Young Girls in Flower in 1919. He finished the first draft of the whole La Recherche in 1922, and told his housekeeper Céleste that he was done and could die. He hadn’t left his bed much during the last years.

His brother Robert made publishing Marcel’s work his mission. Tough job as Proust never reviewed Time Regained and added corrections and additions with sticked bands of paper. The last volume of La Recherche, Time Regained, was published in 1927. Then, Robert published Marcel’s correspondence. Céleste Albaret’s book of souvenirs was published in 1973 and it’s a gold mine of information.

It was a fascinating exhibition with a lot of information and things on display. Paintings, posters, pictures, maps and scale models were numerous and all accompanied by useful explanations. I loved it and I’m not the only one. There were a lot of visitors, which explained the poor pictures. It wasn’t easy to take them.

I will post the pictures about people who mattered in Proust’s life and inspired characters in La Recherche and I hope I’ll have time to post about Paris in La Recherche, the second part of the exhibition.

Albertine Gone by Marcel Proust

The Sweet Cheat Gone (Albertine Gone) by Marcel Proust. (1925) In Search of Lost Time, volume 6. Original French title: Albertine disparue.

Before diving into Albertine Gone by Marcel Proust, some information. I have read it in French, of course. Then I downloaded the cheapest translation available, the Scott Moncrief one. All the quotes in English come from this translation.

In the fifth volume of In Search of Lost Time, the Narrator acts like an insufferable stalker and control freak with Albertine, who now lives with him. Imagine what it must have meant at the beginning of the 20th century, even if, officially, she was staying at his mother’s house. Here are my two billets about The Captive: billet one and billet two.

It took me nine years to move from The Captive to Albertine Gone. In this volume, Albertine leaves him and moves out. How I understand her. Before he can go after her and make her change her mind, she dies in an accident. (Albertine may have been modeled after Alfred Agostinelli, Proust’s flame, killed in an airplane accident in 1914.)

The first part of the volume is about the Narrator’s grief and his relentless research to understand once for all if Albertine was a lesbian and if she cheated on him. Yes, to both. He gets his answer after torturing us with soul wrenching what-ifs, sending out his valet to investigate Albertine’s last days, questioning her girlfriend Andrée, etc. The Narrator is sick with jealously and he seems to be missing Albertine only marginally, because he didn’t get all his answers before her death. Sometimes I felt like he was grieving because grief was what he was supposed to feel and not what he was actually feeling. The Narrator was such a gossip.

However, Proust wrote excellent passages about grief, the recovering process and the Narrator’s feelings. There are beautiful thoughts about memories of people who passed away and what remains of them after they’re gone.

| On dit quelque fois qu’il peut subsister quelque chose d’un être après sa mort, si cet être était un artiste et mit un peu de soi dans son œuvre. C’est peut-être de la même manière qu’une sorte de bouture prélevée sur un être, et greffée au cœur d’un autre, continue à y poursuivre sa vie même quand l’être d’où elle avait été détachée a péri. | We say at times that something may survive of a man after his death, if the man was an artist and took a certain amount of pains with his work. It is perhaps in the same way that a sort of cutting taken from one person and grafted on the heart of another continues to carry on its existence, even when the person from whom it had been detached has perished |

Then he starts going out again and traveling to Venice. He reconnects with his high society friends and tells us what have become of our former acquaintances: Gilberte, Robert de Saint-Loup, the Baron de Charlus, Madame de Guermantes…He’s found his wits and his irony again and this reader thought, “Yay we’re back to socializing and watching people with a magnifying glass!”

We’re back to witty observations and come-backs, this is the Proust I love.

| Le snobisme est, pour certaines personnes, analogue à ces breuvages agréables dans lesquels ils mêlent des substances utiles. | Snobbishness is, with certain people, analogous to those pleasant beverages with which they mix nutritionus substances |

It’s like having coffee with your parents when they start telling you all the news of people you used to know and have lost contact with because you moved out of your hometown. All distant cousins, uncles, acquaintances, neighbors, friends of friends. Who got married, who got sick, blah blah blah. Only Proust says it with a lot more style.

Although you don’t read In Search of Lost Time for the plot, I won’t spoil your reading and tell you the breaking news about Gilberte and Robert de Saint-Loup that are dropped like bombs in this volume.

In Albertine Gone, Proust also makes peace with homosexuality. In the first volumes, it’s described as something unnatural to be ashamed of. Towards the end of this volume, Proust says that Charlus loves doing visits with Morel because he feels like he’s remarried. He loves acting as a couple. This passage is explicit about the Narrator’s views on homosexuality and very modern:

| Personnellement, je trouvais absolument indifférent au point de vue de la morale qu’on trouvât son plaisir auprès d’un homme ou d’une femme, et trop naturel et humain qu’on le cherchât là où on pouvait le trouver. | As far as morality was concerned, it was indifferent to me whether one finds their pleasure with a man or a woman. I found it only too natural and human to seek pleasure where it could be found. (my translation) |

A century later, I wish this sentiment were more widely spread. It would avoid a lot of bullying and heartaches. These two passages about Charlus and this statement about homosexuality are missing from the Scott Moncrief translation. I don’t know if they were censored or if Scott Moncrief worked on a French version that didn’t include these paragraphs.

Albertine disparue isn’t the easiest volume to read, at least for me. It is nonetheless a masterpiece and I have bright memories of Le Temps retrouvé, the next and last volume.

Monsieur Proust’s Library by Anka Muhlstein – a delight for all Proust lovers

Monsieur Proust’s Library by Anka Muhlstein (2012) French title: La bibliothèque de Marcel Proust.

It isn’t enough that he names or quotes the great writers of the past: he has absorbed them; they are an integral part of his being, to the point of participating in its creation. As such their works will survive, not in the immutable way great monuments endure, but constantly rediscovered and reinterpreted thanks to Proust’s unexpected, playful, and intensely personal take on different masterpieces. One of the great joys of reading La Recherche is to disentangle the rich and diverse contributions of the past.

Marcel Proust was born in July 10th, 1871. We are now celebrating the 150th anniversary of his birth and Open Press has published a new edition of Anka Muhlstein’s Monsieur Proust’s Library. It has new illustrations by Andreas Gurewich.

In a slim volume (129 pages), Anka Muhlstein explores Proust and literature. On one side, there’s Proust as a reader and on the other side, there’s literature in In Search of Lost Time, or as French fans call it, La Recherche.

I had a lot of fun going through Proust’s first bookish loves and discovering which foreign writers he admired. We know from La Recherche that Racine, Balzac, Mme de Sévigné and Saint-Simon were among his favorite writers. When you’ve read Proust and seen his style, it’s hard to believe that Proust as a reader enjoyed books with lots of action, like Capitaine Fracasse or novels by Alexandre Dumas.

I knew he was fascinated and influenced by John Ruskin. He translated his work into French, without knowing the English language. His mother, who was fluent in English, helped him and he learned how to read English on the go. He could read but he couldn’t speak. How incredible is that? I didn’t know that he was influenced by Dickens, Hardy and Eliot and loved Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky.

Proust was a great reader and the characters in his books are avid readers too. They all read but the Narrator sort them out between good and bad readers. In this chapter, Muhlstein picks characters in La Recherche and shows who’s a good reader in Proust’s opinion and who is not. Some are even an opportunity for Proust to convey his ideas about reading and literary criticism.

Mme de Villeparisis’s opinions about writers are a spoof of the theories of the great literary critic Sainte-Beuve, who held that knowing an author’s character, morals, religion, and comportment was indispensable for assessing the value of his work. This theory was so abhorrent to Proust that he wrote Contre Sainte-Beuve, arguing passionately that it represented the negation of all that a true writer is about. According to Proust, an artist does not express his inner self—the self that is never exposed in everyday life and is the only self that matters—in conversation, or even in letters. To look at the artist’s life in order to judge the work is absurd.

Unbeknown to be, I’ve always had the same opinion as Proust. How cool is that?

The chapter about the Baron de Charlus as a reader was enlightening too. He’s the homosexual character in La Recherche and an excellent reader. He bonds with the Narrator’s grand-mother over Madame de Sévigné. She sees in him a good, erudite and sensitive reader. In this chapter, Muhlstein demonstrates how much Balzac is embedded in Proust’s text. I discovered that Proust’s favorite works by Balzac are Girl With the Golden Eyes, a lesbian story, A Passion in the Desert, a strange love for panther, Lost Illusions, with Vautrin in love with Lucien de Rubempré and Sarrasine. I didn’t remember that Balzac had homosexual characters.

Another discovery for me was about Racine’s innovative ways with the French language. For me, Corneille and Racine are boring 17th century playwrights stuck in alexandrines. This chapter was truly eye-opening and the explanations about Proust’s fascination for Phèdre were very interesting.

The chapter on the Goncourt brothers was useful as their Journal was a source of information about the French literary world of their time. Proust won the Goncourt Prize in 1919 for In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower.

A book about Proust and literature had to include a chapter about Bergotte, the great writer in La Recherche. It’s modeled after Anatole France, a very famous writer of the time that nobody reads anymore although Proust was convinced that France/Bergotte would reach immortality. Bergotte did as a character thanks to his author.

Proust has created a prodigiously interwoven universe,the form and complexity of which do not reveal themselves easily; but fortunately, it is a universe within which are to be found planets—the worlds of the Guermantes, the Verdurins, and the Narrator’s family, for example—inhabited by a diverse population of characters in turn moving, entertaining, hilarious, and cruel, to which readers are readily attracted. The same may be said of the complex world of literature that Proust himself inhabited.

As always with Proust, I’m amazed at how much I remember of the characters in La Recherche. They stayed with me and when Anka Muhlstein evokes a character or a scene, I know whom or what she’s referring to. I loved her short book about Proust and literature because it is accessible to common readers like me. You don’t need a PhD in literature to read it and it’s an enjoyable and instructive journey into Proust’s library.

Many thanks to Other Press for sending me a free copy of this affectionate book about La Recherche.

I’ve read it at the same time I went to Paris and visited the recently reopened Musée Carnavalet. They have made a whole room about Proust, since they have his bed in their collection. I wish they had redone the corked walls as well, to help us understand the atmosphere in which he wrote.

PS: Tamara at Thyme for tea organizes Paris in July again and that’s an opportunity for me to contribute to her event.

A Summer With Proust – “Reading is a friendship”

A Summer With Proust by Antoine Compagnon, Raphaël Enthoven, Michel Erman, Adrien Goetz, Nicolas Grimaldi, Julia Kristeva, Jérôme Prieur and Jean-Yves Tadié. (2014) Not available in English. Original French title: Un été avec Proust.

La lecture est une amitié.

(Reading is a friendship)

Marcel Proust

In 2013, to celebrate the centenary of the publication of Un amour de Swann by Marcel Proust (Swann’s Way, in English translation), France Inter broadcasted a series of moments entitled A summer with Proust.

In 2013, to celebrate the centenary of the publication of Un amour de Swann by Marcel Proust (Swann’s Way, in English translation), France Inter broadcasted a series of moments entitled A summer with Proust.

Several Proust specialists talked about a side of A la Recherche du temps perdu. (In Search of Lost Time) In French, this masterpiece’s pet name is La Recherche. The panel was composed of Antoine Compagnon, Raphaël Enthoven, Michel Erman, Adrien Goetz, Nicolas Grimaldi, Julia Kristeva, Jérôme Prieur and Jean-Yves Tadié. They are teachers, philosophers, writers, essayists, film-makers or historians, all Proust lovers.

Each of them has a section in the book and writes about Proust or something in La Recherche. The topics are various: Time, characters, love, imagination, places, Proust and philosophers and arts. All chapters are structured the same way: a quote, a short introduction, an essay and a longer quote to illustrate the essay. They make Proust easy and the burin of their love for Proust chips away the ivory tower where this monument of literature has been locked into. They demystify Proust, the author of a literary cathedral.

This team of writers knows La Recherche in and out and addresses all readers with maestro. I imagine that the newcomer will want to start reading Proust after this appetizer. The Proust reader will experience a mise en abyme, living the madeleine episode while reading about reading Proust.

I opened this billet with a quote by Proust stating that La lecture est une amitié and this is exactly how I feel about literature in general and Proust in particular. Like the writers of A Summer With Proust, I have a long and standing friendship with La Recherche. Of course, I’m far from being as literate as they are about Proust but reading A Summer With Proust is like receiving a letter full of news from old friends who would live on another continent.

I discovered Proust when I was in high school. I read it slowly, La Recherche is not a book you devour and it required a lot of attention. This slow rhythm mixed with the presence of characters coming in and out of the pages all along the volumes is such that the characters and events stay with you. I started to read it again as an adult. (See my Reading Proust page) and I got reacquainted with a world I had not forgotten.

Like all readers I have experienced this: I read a book I enjoy immensely and a few months later, I don’t really remember it, its plot or its characters. For my memory and my senses, some books are like the rain of a summer storm. I get drenched, I get dry and I move on. Lots of rain and pleasure at the time I read, but most of the flow is flushed from my memory. Storms don’t help with groundwater, moderate rains do.

La Recherche is not a storm, it’s a long, persistent and warm drizzle. It reached my bones, penetrated my memory the first time I read it and settled in me. I developed a familiarity with the characters of La Recherche and I can only compare it to crime fiction series, with their recurring character. When you open a new volume of the series, you’re on familiar grounds, happy to spend some more time with the lead character. When I started A Summer With Proust, I re-connected to Proust’s world immediately, like you do when you meet up with good friends, even if you haven’t seen them for a long time. The reconnection is instantaneous.

In La Recherche, Proust is the master of all masters. He wrote a book about the power of imagination, about memory and its effect on us. Through the power of his memories, his literary skills and his intelligence, he wrote a masterpiece that dissects the workings of memories and sensorial experiences on our beings and at the same time imprints himself and his lost world in our souls and memories. His experience helps us understand our experience.

Proust left us keys to enter into our memories, analyze our feelings and enjoy little moments in life. For he is also the writer who dissects small moments, sees the beauty in them and tells us that beauty is within our reach if we pay enough attention.

In other words, it’s good to be friends with La Recherche, a book that gives its friendship freely to readers who seek for it.

Literary escapade: Proust and the centennial of his Prix Goncourt

In 1919, Proust won the most prestigious French literary prize, the Prix Goncourt for the second volume of In Search of Lost Time, In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower. Gallimard was Proust’s publisher.

In 1919, Proust won the most prestigious French literary prize, the Prix Goncourt for the second volume of In Search of Lost Time, In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower. Gallimard was Proust’s publisher.

To celebrate this centenary, the Gallerie Gallimard in Paris set up an exhibition around this event. Did you know that Proust’s win was a scandal at the time?

In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower was in competition with Wooden Crosses by Roland Dorgelès, a book about the trenches and WWI. The public was in favor of Mr Dorgelès and his patriotic novel. (I’ve never read it, I can’t tell anything about it)

Proust was considered too old for the prize. There have been arguments about the Goncourt brothers’ intentions when they made the prize for a “young talent”. Who’s young, the writer or the talent? Proust was too rich and the 5000 francs of the prize would have been better spent on a poor writer. Proust was too involved in the high society, even if at the time he wrote In Search in Lost Time, he was mostly living in solitude. Proust was too odd with his strange living habits, his book was too verbose and he did not fight in the war.

There were a lot of arguments against his winning but none of them were about the literary quality of his novel. And the Académie Goncourt, in charge of picking the winner, concentrated on the literary aspects of the book.

After the 1919 Prix Goncourt was awarded, the press went wild against Proust. The exhibition shows a collage of press articles of the time, all coming from Proust’s own collection.

According to Thierry Laget, who wrote Proust, Prix Goncourt, une émeute littéraire, (Proust, Goncourt Prize, a literary scandal), the violence and the form of the attacks against Proust were like a campaign on social networks today. I might read his book, I’m curious about the atmosphere of the time and what Laget captures about it.

There was a wall about Gaston Gallimard who founded what would become the Gallimard publishing house in 1911. Gallimard convinced Proust to let them publish In Search of Lost Time and In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower was Gallimard’s first Prix Goncourt.

The exhibition displays the letter that the Académie Goncourt sent to Proust to officially inform him that he won. I found it simple, unofficial looking.

There were two previously unreleased drawings of Proust like this one by Paul Morand in 1917. It was made at the Ritz and it represents Proust, Morand and Laure de Chévigné, one of the women who inspired the Duchesse de Guermantes.

And the other one was of Proust on his death bed in 1921.

It’s a small exhibition that lasts only until October 23rd, rush for it if you’re a Proust fan and are in Paris during that time.

Saturday literary delights, squeals and other news

For the last two months, I’ve been buried at work and busy with life. My literary life suffered from it, my TBW has five books, I have a stack of unread Télérama at home, my inbox overflows with unread blog entries from fellow book bloggers and I have just started to read books from Australia. Now that I have a blissful six-days break, I have a bit of time to share with you a few literary tidbits that made me squeal like a school girl, the few literary things I managed to salvage and how bookish things came to me as if the universe was offering some kind of compensation.

I had the pleasure to meet again with fellow book blogger Tom and his wife. Tom writes at Wuthering Expectations, renamed Les Expectations de Hurlevent since he left the US to spend a whole year in Lyon, France. If you want to follow his adventures in Europe and in France in particular, check out his blog here. We had a lovely evening.

I also went to Paris on a business trip and by chance ended up in a hotel made for a literature/theatre lovers. See the lobby of the hotel…

My room was meant for me, theatre-themed bedroom and book-themed bathroom

*Squeal!* My colleagues couldn’t believe how giddy I was.

Literature also came to me unexpectedly thanks to the Swiss publisher LaBaconnière. A couple of weeks ago, I came home on a Friday night after a week at top speed at work. I was exhausted, eager to unwind and put my mind off work. LaBaconnière must have guessed it because I had the pleasure to find Lettres d’Anglererre by Karel Čapek in my mail box. What a good way to start my weekend. *Squeal!* It was sent to me in hope of a review but without openly requesting it. Polite and spot on since I was drawn to this book immediately. LaBaconnière promotes Central European literature through their Ibolya Virág Collection. Ibolya Virág is a translator from the Hungarian into French and LaBaconnière has also published the excellent Sindbad ou la nostalgie by Gyula Krúdy, a book I reviewed both in French and in English. Last week, I started to read Lettres d’Angleterre and browsed through the last pages of the book, where you always find the list of other titles belonging to the same collection. And what did I find under Sindbad ou la nostalgie? A quote from my billet! *Squeal!* Now I’ve never had any idea of becoming a writer of any kind but I have to confess that it did something to me to see my words printed on a book, be it two lines on the excerpt of a catalogue. Lettres d’Angleterre was a delight, billet to come.

Literature also came to me unexpectedly thanks to the Swiss publisher LaBaconnière. A couple of weeks ago, I came home on a Friday night after a week at top speed at work. I was exhausted, eager to unwind and put my mind off work. LaBaconnière must have guessed it because I had the pleasure to find Lettres d’Anglererre by Karel Čapek in my mail box. What a good way to start my weekend. *Squeal!* It was sent to me in hope of a review but without openly requesting it. Polite and spot on since I was drawn to this book immediately. LaBaconnière promotes Central European literature through their Ibolya Virág Collection. Ibolya Virág is a translator from the Hungarian into French and LaBaconnière has also published the excellent Sindbad ou la nostalgie by Gyula Krúdy, a book I reviewed both in French and in English. Last week, I started to read Lettres d’Angleterre and browsed through the last pages of the book, where you always find the list of other titles belonging to the same collection. And what did I find under Sindbad ou la nostalgie? A quote from my billet! *Squeal!* Now I’ve never had any idea of becoming a writer of any kind but I have to confess that it did something to me to see my words printed on a book, be it two lines on the excerpt of a catalogue. Lettres d’Angleterre was a delight, billet to come.

Now that I’m off work, I started to read all the Téléramas I had left behind. The first one I picked included three articles about writers I love. *Squeal!* There was one about visiting Los Angeles and especially Bunker Hill, the neighborhood where John Fante stayed when he moved to Los Angeles. I love John Fante, his sense of humor, his description of Los Angeles and I’m glad Bukowski saved him from the well of oblivion. It made me want to hop on a plane for a literary escapade in LA. A few pages later, I stumbled upon an article about James Baldwin whose novels are republished in French. Giovanni’s Room comes out again with a foreword by Alain Mabanckou and there’s a new edition of Go Tell It on the Mountain. Two books I want to read. And last but not least, Philip Roth is now published in the prestigious La Pléiade edition. This collection was initially meant for French writers but has been extended to translated books as well. I don’t know if Roth is aware of this edition but for France, this is an honor as big as winning the Nobel Prize for literature, which Roth totally deserves, in my opinion.

Now that I’m off work, I started to read all the Téléramas I had left behind. The first one I picked included three articles about writers I love. *Squeal!* There was one about visiting Los Angeles and especially Bunker Hill, the neighborhood where John Fante stayed when he moved to Los Angeles. I love John Fante, his sense of humor, his description of Los Angeles and I’m glad Bukowski saved him from the well of oblivion. It made me want to hop on a plane for a literary escapade in LA. A few pages later, I stumbled upon an article about James Baldwin whose novels are republished in French. Giovanni’s Room comes out again with a foreword by Alain Mabanckou and there’s a new edition of Go Tell It on the Mountain. Two books I want to read. And last but not least, Philip Roth is now published in the prestigious La Pléiade edition. This collection was initially meant for French writers but has been extended to translated books as well. I don’t know if Roth is aware of this edition but for France, this is an honor as big as winning the Nobel Prize for literature, which Roth totally deserves, in my opinion.

Romain Gary isn’t published in La Pléiade (yet) but he’s still a huge writer in France, something totally unknown to most foreign readers. See this display table in a bookstore in Lyon.

His novel La Promesse de l’aube has been made into a film that will be on screens on December 20th. It is directed by Eric Barbier and Charlotte Gainsbourg plays Nina, Gary’s mother and Pierre Niney is Romain Gary. I hope it’s a good adaptation of Gary’s biographical novel.

Romain Gary was a character that could have come out of a novelist’s mind. His way of reinventing himself and his past fascinates readers and writers. In 2017, at least two books are about Romain Gary’s childhood. In Romain Gary s’en va-t-en guerre, Laurent Seksik explores Gary’s propension to create a father that he never knew. I haven’t read it yet but it is high on my TBR.

The second book was brought in the flow of books arriving for the Rentrée Littéraire. I didn’t have time this year to pay attention to the books that were published for the Rentrée Littéraire. I just heard an interview of François-Henri Désérable who wrote Un certain M. Piekielny, a book shortlisted for the prestigious Prix Goncourt. And it’s an investigation linked to Gary’s childhood in Vilnius. *Squeal!* Stranded in Vilnius, Désérable walked around the city and went in the street where Gary used to live between 1917 and 1923. (He was born in 1914) In La promesse de l’aube, Gary wrote that his neighbor once told him:

| Quand tu rencontreras de grands personnages, des hommes importants, promets-moi de leur dire: au n°16 de la rue Grande-Pohulanka, à Wilno, habitait M. Piekielny. | When you meet with great people, with important people, promise me to tell them : at number 16 of Grande-Pohulanka street in Wilno used to live Mr Piekielny. |

Gary wrote that he kept his promise. Désérable decided to research M. Piekielny, spent more time in Vilnius. His book relates his experience and his research, bringing back to life the Jewish neighborhood of the city. 60000 Jews used to live in Vilnius, a city that counted 106 synagogues. A century later, decimated by the Nazis, there are only 1200 Jews and one synagogue in Vilnius. Of course, despite the height of my TBR, I had to get that book. I plan on reading it soon, I’m very intrigued by it.

Gary wrote that he kept his promise. Désérable decided to research M. Piekielny, spent more time in Vilnius. His book relates his experience and his research, bringing back to life the Jewish neighborhood of the city. 60000 Jews used to live in Vilnius, a city that counted 106 synagogues. A century later, decimated by the Nazis, there are only 1200 Jews and one synagogue in Vilnius. Of course, despite the height of my TBR, I had to get that book. I plan on reading it soon, I’m very intrigued by it.

Despite all the work and stuff, I managed to read the books selected for our Book Club. The October one is Monsieur Proust by his housekeeper Céleste Albaret. (That’s on the TBW) She talks about Proust, his publishers and the publishing of his books. When Du côté de chez Swann was published in 1913, Proust had five luxury copies made for his friends. The copy dedicated to Alexandra de Rotschild was stolen during WWII and is either lost or well hidden. The fifth copy dedicated to Louis Brun will be auctioned on October 30th. When the first copy dedicated to Lucien Daudet was auctioned in 2013, it went for 600 000 euros. Who knows for how much this one will be sold? Not *Squeal!* but *Swoon*, because, well, it’s Proust and squeals don’t go well with Proust.

Although Gary’s books are mostly not available in English, I was very happy to discover that French is the second most translated language after English. Yay to the Francophonie! According to the article, French language books benefit from two cultural landmarks: the Centre National du Livre and the network of the Instituts français. Both institutions help financing translations and promoting books abroad. I have often seen the mention that the book I was reading had been translated with the help of the Centre National du Livre.

I mentioned earlier that the hotel I stayed in was made for me because of the literary and theatre setting. I still have my subscription at the Théâtre des Célestins in Lyon and I’ve seen two very good plays. I wanted to write a billet about them but lacked the time to do so.

The first one is Rabbit Hole by Bostonian author David Lindsay-Abaire. The French version was directed by Claudia Stavisky. The main roles of Becky and Howard were played by Julie Gayet and Patrick Catalifo. It is a sad but beautiful play about grieving the death of a child. Danny died in a stupid car accident and his parents try to survive the loss. With a missing member, the family is thrown off balance and like an amputated body, it suffers from phantom pain. With delicate words and spot-on scenes, David Lindsay-Abaire shows us a family who tries to cope with a devastating loss that shattered their lived. If you have the chance to watch this play, go for it. *Delight* On the gossip column side of things, the rumor says that François Hollande was in the theatre when I went to see the play. (Julie Gayet was his girlfriend when he was in office)

The second play is a lot lighter but equally good. It is Ça va? by Jean-Claude Grumberg. In French, Ça va? is the everyday greeting and unless you genuinely care about the person, it’s told off-handedly and the expected answer is Yes. Apparently, this expression comes from the Renaissance and started to be used with the generalization of medicine based upon the inspection of bowel movements. (See The Imaginary Invalid by Molière) So “Comment allez-vous à la selle” (“How have your bowel movements been?”) got shortened into Ça va? Very down-to-earth. But my dear English-speaking natives, don’t laugh out loud too quickly, I hear that How do you do might have the same origin…Back to the play.

In this play directed by Daniel Benoin, Grumberg imagines a succession of playlets that start with two people meeting up and striking a conversation with the usual Ça va? Of course, a lot of them end up with dialogues of the deaf, absurd scenes, fights and other hilarious moments. Sometimes it’s basic comedy, sometimes we laugh hollowly but in all cases, the style is a perfect play with the French language. A trio of fantastic actors, François Marthouret, Pierre Cassignard and Éric Prat interpreted this gallery of characters. *Delight* If this play comes around, rush for it.

To conclude this collage of my literary-theatre moments of the last two months, I’ll mention an interview of the historian Emmanuelle Loyer about a research project Europa, notre histoire directed by Etienne François and Thomas Serrier. They researched what Europe is made of. Apparently, cafés are a major component of European culture. Places to sit down and meet friends, cultural places where books were written and ideas exchanged. In a lot of European cities, there are indeed literary cafés where writers had settled and wrote articles and books. New York Café in Budapest. Café de Flore in Paris. Café Martinho da Arcada in Lisbon. Café Central in Vienna. Café Slavia in Prague. Café Giubbe Rosse in Florence. (My cheeky mind whispers to me that the pub culture is different and might have something to do with Brexit…) It’s a lovely thought that cafés are a European trademark, that we share a love for places that mean conviviality. That’s where I started to write this billet, which is much longer than planned. I’ll leave you with two pictures from chain cafés at the Lyon mall. One proposes to drop and/or take books and the other has a bookish décor.

Literature and cafés still go together and long life to the literary café culture!

I wish you all a wonderful weekend.

Proust therapy

Recently I had one of those days off where you pack do many things to do that you wish you had been in the office instead. At the end of the day, I felt stressed out and frazzled by the pace of the day. I needed something to calm me down, especially since I was going to the theatre that night and wanted to enjoy myself.

Recently I had one of those days off where you pack do many things to do that you wish you had been in the office instead. At the end of the day, I felt stressed out and frazzled by the pace of the day. I needed something to calm me down, especially since I was going to the theatre that night and wanted to enjoy myself.

That’s where the book/CD of Ca peut pas faire de mal came to my rescue. Ca peut pas faire de mal (It can’t hurt) is a radio show on France Inter where Guillaume Gallienne reads excerpts of books and discusses a writer. It is a marvelous show and marketing people made a CD/book out of it. Lucky me, I got one for Christmas and it’s about Proust, Hugo and Madame de Lafayette.

I put the CD in the car and I forgot the stress of my day. Proust read by Gallienne makes you truly understand where all the fuss about Proust comes from. The passages recorded belong to different volumes of A la recherche du temps perdu and I remembered these scenes. This is Proust’s magic: hundreds of pages of literature and the characters stay with you, scenes are tattooed in your memory and emotions are lasting. Cocteau said about Proust:

| Il y a des oeuvres courtes qui paraissent longues; la longueur de Proust me paraît courte. | There are short works that seem long; Proust’s length seems short to me. |

I share that feeling but I’ll say that some volumes are easier than others.

In his introduction to the show, Gallienne recalls:

Marcel Proust, I discovered him through my grand-mother. She told me “Proust, he’s one of the most irresistible things in the world” I said “Is he?” She said “Proust is hilarious” Ah! I expected anything but this definition and later on, Jean-Yves Tadié, Proust biographer told me “Oh! Discovering Proust thanks to your grand-mother, it’s a very good start.” So let’s laugh with Marcel!

He then starts reading several excerpts showing how Proust practices the whole rainbow of funny from sunny comedy to black humour and through irony, piques and erudite puns. One excerpt relates how the Baron the Charlus walks his bourgeois lover Morel through the intricacies of the aristocratic hierarchy. Hilarious. Another one brings to life Madame Verdurin and her clique. Proust describes her facial expressions, her verbal tics and her behaviour among her beloved followers. Gallienne reads the descriptions, plays the dialogues and turns a written portrait into a flesh and blood person.

There’s also the masterful scene in Le Côté de Guermantes when the duke and duchess de Guermantes reveal their true self. They’re self-centred to the point of rudeness and insensitivity. Within a few pages, with a simple situation and banal dialogues, the reader understands that not even family and friends dying would prevent the Guermantes to attend a party. They’re appalling, as I mentioned in this billet. Other passages are about Françoise (the servant), Marcel’s beloved grand-mother and homosexuality. The last one is a letter from the front written by the Narrator’s friend Robert de Saint-Loup. Gallienne says it prefigures Céline. He may be right.

In short passages, the CD gives you a taste of A la recherche du temps perdu. Gallienne reads with gourmandise. That’s a French word I have a hard time translating into English. Like plaisir. If I look up gourmandise in the dictionary, I come up with greed and gluttony which are negative words. They’re flaws or sins. True, in French gourmandise means gluttony as well. But not only. In a more figurative sense, it also means appetite in the most positive way. It goes with innocent pleasure, like in my son’s sentence En avant le plaisir! I never know how to express this in English.

So Gallienne reads Proust with gourmandise in a tone that suggests he’s having a treat, relishing in the turn of sentences, the delicious and old-fashioned subjonctif passé. He reads like a kid eats sweets, with abandonment and gusto. Words roll around his tongue, like he’s savouring a fancy meal or tasting a great wine. If you want to discover Proust, if you’re curious about how Proust sounds in French, then you need to hear Gallienne read these passages. You’ll want to read or reread Proust.

After this, Proust fest, I was calm. All the irritating moments of my day had faded away. I was available and ready to see The Village Bike by Penelope Skinner. That was my Proust therapy. The world would be a quieter place with more literature therapies. Perhaps it’s too ambitious but at least it benefited Penelope Skinner: I was ready to leave my day behind and enter the world she had created for us.

I finished reading La Prisonnière, eventually

La Prisonnière by Marcel Proust. 1929 English title: The Captive

I ended my previous post about The Captive with the following paragraph:

Chapter 2 is entitled: Les Verdurin se brouillent avec M. de Charlus. (The Verdurins quarrel with M. de Charlus). Relief. He’s socializing again and we’ll get some fresh air.